Burgeoning research suggests that trauma can be passed intergenerationally. This article examines the relationship between intergenerational trauma and epigenetics.

Related articles: Assessing and Treating Trauma, Assessing and Treating PTSD, Case Study: Healing from Trauma as a Soldier.

Introduction

Imagine this scenario. It’s the early 1980s. You are a new-ish psychotherapist who has been helping clients with trauma for a few years now, many of them Vietnam veterans. You acknowledge that many of the Vietnam war vets are still troubled, but you secretly wonder if they just need to “pull themselves up by their bootstraps” and get on with it. You have had a quick look at the newly-published DSM-III which, for the first time, proclaims – in the form of the new disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD – that a threat can continue to influence the body long after it is removed. “Preposterous!” you think, “How is that possible?”

Fast forward to the 2020s. You are now in pre-retirement phase, having had a rewarding but sometimes intense career helping people with all sorts of trauma. You keep up with the latest developments in your field and have learned about studies published in recent years which, incredibly, seem to show that one generation’s trauma leaves biological traces in their children, and even their children’s children. Your reaction? “Who knew?” you think. “It will be up to the next generation of mental health professionals to deal with this. It’s complicated and scary.”

And with these reflections, you would be pretty much spot-on. This article examines the relationship between intergenerational trauma and epigenetics, the newly-emerging science showing that trauma is able to influence not just those who experience the trauma, but also subsequent generations – including unborn ones – by altering the expression, or “reading” of their genes (though not their actual DNA, or genetic material). We look at studies which have helped scientists to put in place various pieces of the epigenetics jigsaw puzzle, but much is still yet to be known.

Trauma and epigenetics: Definitions

Let’s get on the same page first with a few definitions.

Trauma

We can define trauma as a person’s emotional response to a tragic and/or life-threatening event, such as an accident, sexual violence, or natural disaster. Long-term trauma can produce effects such as intrusive memories, avoidance, changes in thinking and mood, and changes in physical and emotional reactions (Valeii, 2024).

Intergenerational trauma

This sort of trauma is defined by the theory that a trauma experienced by one person in a family – for example a parent or grandparent – can be passed down to future generations because of the way that trauma epigenetically alters genes (Valeii, 2024).

Epigenetics

We can explain epigenetics as a field focused on how behaviours and the environment influence the way a person’s genes work, affecting genetic expression by “turning on and off” their genes. Infection, cancer, and prenatal nutrition are all ways that epigenetic changes can affect health (Valeii, 2024; Ryder, 2022).

Re-evaluating history: Studies which suggest epigenetic change

The field of epigenetics is newly emerging, but what’s interesting about it is that the new understandings have been helping us to shed light on historical events that we can now re-analyse as epigenetics in action. We look at the American Civil War POWs, the Dutch Hunger Winter, the 9/11 babies, and the Holocaust survivors and their children.

Civil war P.O.W.s, revisited

The finding that our children and grandchildren are shaped not only by the genes we pass down to them, but by our experiences as well – that is, epigenetic changes – has also been supported by a new look at old historical records. In 1864, near the end of the Civil War in the United States, conditions for Union prisoners of war in Confederate prisons were at their most inhumanely atrocious. Apart from near starvation (prisoners existing on corn alone), lack of sanitation and other basic essentials, the men were crowded into the amount of square footage equal to a grave. Many died. Those walking skeletons who survived returned to their northern states with serious health issues, poor job prospects, and much shorter life expectancies than their fellow soldiers who had not been imprisoned.

Unfortunately, the bad news did not stop there. When the health records of nearly 4,000 children whose fathers had been POWs were compared with over 15,000 children of Civil War vets who had not been imprisoned, the sons of POWs had an 11% higher mortality rate than the sons of non-POWs. Even the subsequent generation – the prisoners’ grandchildren, who (like their parents) did not suffer the hardships of the Civil War and were provided for much more bountifully in their childhoods – also suffered higher rates of premature mortality than the general population of the time (Henriques, 2019).

Dutch Winter Hunger

Another oft-cited historical example arises from the Nazi occupation of The Netherlands in October 1944. The Nazis blocked food supplies, throwing much of the Dutch population into famine. By the time the Dutch were liberated in May 1945 – seven or eight months later – at least 20,000 had died of starvation. Naturally, pregnant women were the most vulnerable, but for our purposes here, what is of interest is the effect of the famine on the unborn children, for the rest of their lives. Scientists found that those who had been in utero during the period were a few pounds heavier than average. The epigenetic hypothesis is that, because they were starving, the women’s bodies automatically (unconsciously) quieted a gene in their unborn children involved in burning the body’s fuel. Those children, at middle age, had higher levels of LDL (the “bad” cholesterol) and triglyceride levels. They also had higher rates of diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and schizophrenia. Digging deeper, the scientists discovered that the children carried a specific chemical mark, an epigenetic one, on one of their genes (Erdelyi, 2022).

9/11: Impact to more than the 3,000 in the towers

Dr. Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at the Icahn school of Medicine at Mount Sinai, was asked by a colleague to help diagnose and monitor 187 pregnant women who had been in the area of the World Trade Center twin towers when the towers collapsed from the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Of course, the women were in shock and at risk of developing PTSD, but Dr. Yehuda wondered whether the foetuses were at risk. The answer to that question accelerated Yehuda’s two-decade-plus study of how adverse experiences of one generation can change future generations through epigenetic pathways.

The 9/11 babies were smaller than usual. Nine months later, 38 of the women came into the clinic for a wellness check. Many of the women were assessed at that stage to have PTSD. Those who did had unusually low levels of the stress-related hormone cortisol, a feature that, while counterintuitive (given its role in the stress response), researchers were coming to associate with PTSD. What astounded Yehuda and her colleagues, though, was that the saliva of the now nine-month-old babies of the women with PTSD. also showed low cortisol – especially those babies from women who were in their third trimester on September 11 – despite the babies not having been born yet when the towers came down (Yehuda, 2022).

Holocaust survivors and their offspring

Scientists look for patterns, and Yehuda and her research team could not help but notice the lower levels of cortisol in the 9/11 babies because a year earlier, they had analysed blood samples of Holocaust survivors, nearly all of whom also had low cortisol levels. Moreover, they compared the survivors’ blood samples with those of Jews who had lived outside of Europe during the Holocaust. The mothers who survived the Holocaust had changes in the sections of their genes that regulate stress response – that is, the cortisol levels; those not subjected to the Holocaust had normal cortisol levels. Importantly, when the Holocaust survivors’ children were also studied, their children who were not born until after the war and so did not experience the Holocaust also had low levels of cortisol (Rozsa, 2023; Yehuda, 2022).

After seeing the changes in cortisol levels for both groups and their after-the-trauma-born children, the hypothesis began to be floated that adverse experiences cause biological changes that carry on to the next generation: in other words, what we now know as epigenetic changes. Ever the cautious scientist, however, Yehuda originally refused to believe that low cortisol levels had anything to do with trauma. Her reticence to acknowledge the association is understandable, given that stress usually causes stress hormones, including cortisol, to rise, not go down (Yehuda, 2022).

The regulatory role of cortisol

It turns out, however, that cortisol is not just the hormone we rely on for that extra sharpening-the-senses “oomph” in fighting an adversary in an acutely stressful moment (think: sabre-tooth tiger chasing you in your incarnation as a caveman). It also seems to play a special regulatory role. Those of us who have lived life in the (stressful) fast lane – and thereby generated a fair bit of cortisol – can attest to the reality that high levels of cortisol and other stress hormones, if sustained for a long time, harm our bodies in multiple ways. A chief impact here is that our immune system weakens, and we experience increased susceptibility to problems such as hypertension. But cortisol may paradoxically also have a protective effect; it shuts down the release of stress hormones (weirdly, including itself!), thus reducing the potential damage to organs and the brain. This trauma-induced feedback loop could, it is hypothesised, reset the cortisol “thermostat” to a lower level (Yehuda, 2022).

Vietnam vets abused as children more likely to develop PTSD

Dr. Yehuda’s research in the 1990s had already shown that Vietnam vets who had been abused as children were more likely to develop PTSD during or after their service than those not abused, and they, too, had surprisingly low levels of cortisol. The link between low cortisol and likely future PTSD. became clear upon realising that, probably, those developing PTSD. had had low cortisol levels prior to their Vietnam experience, so when the event(s) of the war happened to them, the cortisol levels in their bodies were too low to tamp down the stress reaction. The adrenalin levels, though, shot up markedly, thus deeply imprinting the memory of the new trauma into their brains, from where it could resurface as nightmares or flashbacks.

Feedback loop explained

We started this article talking about epigenetics, and we need one more finding to connect the dots. Yehuda’s research team connected trauma exposure to low cortisol to future PTSD when they discovered that those Vietnam vets with PTSD had a greater number of glucocorticoid receptors, the proteins to which cortisol binds to exert its various influences on body and mind; the extra receptors gave the vets a greater sensitivity to cortisol. It didn’t, they found out, take much of an increase to effect a disproportionate bodily reaction. Around the time of these studies, it began to be evident that what our genes put out is sensitive to factors not written directly into the genetic code (the DNA); variations in other factors (meaning, in the environment) influence how those genes express. Thus, through the action of other identified processes – specifically, methylation – the receptors’ sensitivity was increased, even though the DNA remained unchanged.

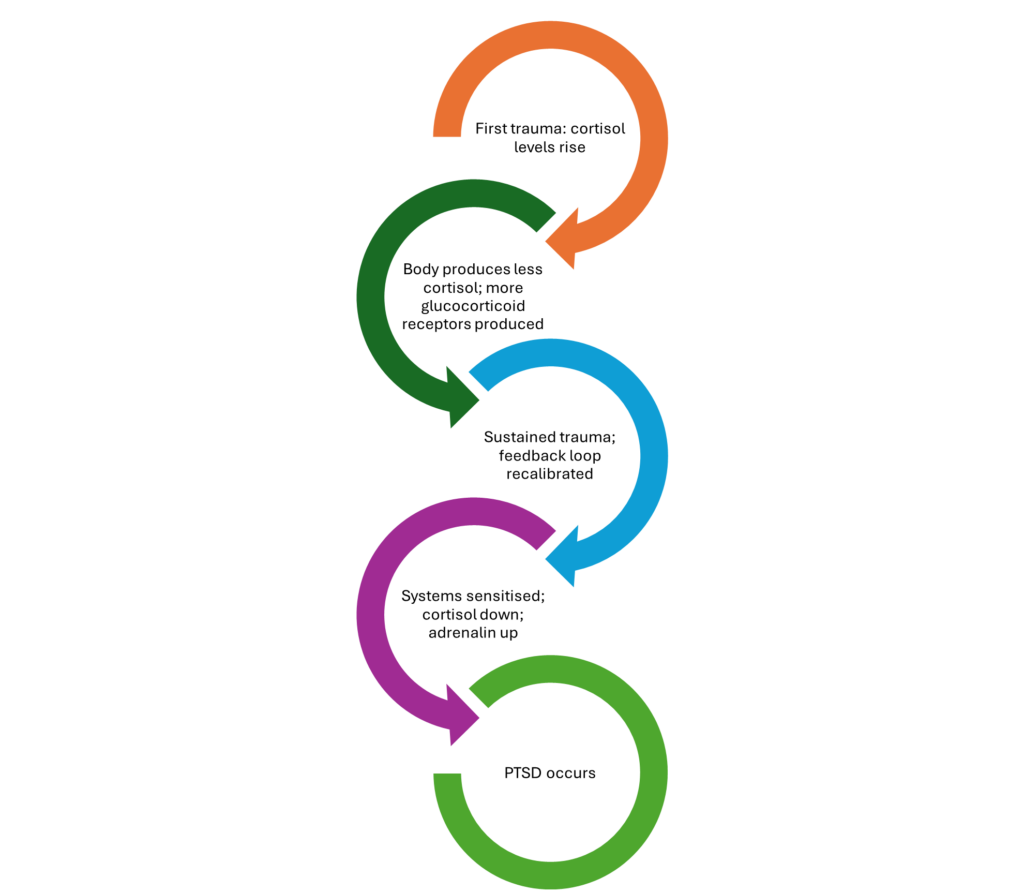

The epigenetic feedback loop, then, appears to go like this. An initial rise in cortisol levels (during the first, ongoing, trauma) prompts the body to eventually produce less of the hormone, which drives up the numbers and responsiveness of glucocorticoid receptors. Epigenetic and other changes kick in with sustained responses to trauma and the feedback loop becomes recalibrated. In those who have already endured trauma, their stress systems are sensitised and their cortisol levels diminished, increasing their adrenaline response to further trauma. PTSD follows (Yehuda, 2022) (see Figure).

Figure: The epigenetic feedback loop of trauma

Troubled offspring in mice and worms

Mice and cherry blossom

It’s not only human beings subject to epigenetic processes. Researchers doing controlled experiments with mice have shown an intergenerational effect of trauma associated with scent. In a 2013 study, researchers blew the scent of cherry blossom (actually, acetophenone) through the cages of adult male mice, sending a current of electric shock to their feet at the same time. After a few repetitions of that, the mice associated the smell of cherry blossoms with pain. Shortly after this investigation, the male mice were bred with females, whose pups became jumpier and more nervous upon smelling cherry blossom than pups whose fathers hadn’t been conditioned to dread the smell.

The experimenters ruled out mice learning about the smell from their parents by having the “jumpy” pups raised by unrelated mice who had never smelled cherry blossom. It turned out that the grandpups of the traumatised males also showed greater sensitivity to the scent, even though neither the pups nor the grandpups had greater sensitivity to other smells: just cherry blossom. Researchers later found chemical markers on a gene encoding a smell receptor, expressed in the olfactory bulb between the nose and the brain. At post-humous dissection of these mice brains, researchers also found more neurons that detect the cherry blossom scent than what control mice had (Henriques, 2019).

Worms

Finally, here, we note the findings from researchers at Princeton University that nematode worms, whose diet consists of decaying organic matter and rotten fruit, occasionally ingest some harmful bacteria, which kills them (perhaps like some human beings that can’t tell a “good” mushroom from a poisonous one in the forest?). What is epigenetically interesting here is that the researchers noticed that, before dying from the harmful bacteria, the worms lay eggs. And the worm offspring consistently avoid the specific bacteria that killed their parent worms! These findings also showed that the behaviour can be transmitted to the worm’s offspring through the fourth generation, giving those generations a survival edge (Erdelyi, 2022).

Likewise, a Swiss researcher, Isabelle Mansuy, was able to show trauma behaviours in mice – manifesting in both molecular and behavioural changes – persisting up to five generations (i.e., breeding carried out for six generations in total, with only the first one being traumatised) (Curry, 2019).

Epigenetics and hope

We’ve recounted fascinating but scary case examples from both human and animal beings to show that, although much is not understood about the mechanisms of how it happens, adverse experiences incurred by one generation can chemically – epigenetically – mark succeeding generations, even while the DNA remains unchanged. These studies leave us with two questions: (1) are epigenetic changes always bad? And (2) can these changes be reversed, so that our ancestors’ past doesn’t affect us so much?

In regard to the first question, Yehuda reminds us that, while it’s tempting to always interpret trauma-induced changes as bad, epigenetic changes might very well be the body’s attempt to prepare offspring for challenges similar to what their parents experienced. Under changed circumstances, however, any survival value of the changes could be diminished or even reversed, so how helpful the changes are depends on the environment encountered by the offspring (Yehuda, 2022).

Mansuy undertook to answer the second question, providing traumatised mice with either a standard (shoebox-size) mouse cage or, for the experimental group, a luxury two-story mouse house, replete with three running wheels and a miniature maze. In 2016, she published findings that the group in the enriched luxury house did not pass the epigenetic trauma mark onto their children, unlike the control group in the standard cage. Similarly, the researchers who traumatised mice with the cherry blossom scent reconditioned their mice to lose their fear of cherry blossoms, and the offspring born after this “treatment” did not have the cherry blossom alteration. They also did not fear the scent. And combat vets with PTSD who responded to CBT treatment showed changes in methylation, the central process we noted above in gene expression alteration (Curry, 2019; Yehuda, 2022).

These findings are hopeful, suggesting that there are ways to interrupt the intergenerational transfer of epigenetic changes. Environmental enrichment and other treatments at the right time might help correct some of the alterations induced by the trauma. And knowledge is ever increasing about how to induce post-traumatic growth (Curry, 2019). We have much to learn – and much yet to apply to human beings from animal experimentation – but every finding gives us one more piece of the jigsaw puzzle toward an ever-clearer picture of a resilient future, despite life’s habit of throwing adversities our way.

Trauma courses

Learn more about how to support clients impacted by trauma with our micro-credential trauma course, Working with Trauma: Interventions That Foster Resilience. This 20-hour program, facilitated by Dr. Cirecie West-Olatunji, teaches you the key issues, current trends and most efficacious interventions in trauma counselling, with a special focus on the effects of trauma on marginalised groups, and how you can support them as a clinician.

Other trauma courses you may be interested in:

- Working with Trauma

- Emotionally Focused Individual Therapy (EFIT) for Trauma: Dancing Tango and Reshaping Self

- Diagnosing Trauma-Related Disorders

- The Traumatic Effects of Disasters

- Principles of Trauma-informed Practice

- The Treatment of Trauma and the Internal Family Systems Model

- Understanding the Link Between Trauma and Addiction

- Counselling Trauma Affected Clients with Diverse Abilities

- Non-Combat Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Veterans: A Focus on Non-Combat Military-Related Trauma

- Case Studies in Trauma

- Systemic Oppression and Traumatic Stress: Evidence-based Social Justice Interventions for Clinicians

- Using Play to Provide Multicultural Trauma Treatment to Adolescents and Kids

- Intimate Partner Violence Solution-Focused Trauma Care

- First Do No Harm: The Need for Trauma-Sensitive Mindfulness

Note: Mental Health Academy members can access 500+ CPD/OPD courses, including many of those listed above, for less than $1/day. If you are not currently a member, click here to learn more and join.

Key takeaways

- Intergenerational trauma is defined by the theory that a trauma experienced by one person in a family – for example a parent or grandparent – can be passed down to future generations because of the way that trauma epigenetically alters genes.

- Epigenetics is a field focused on how behaviours and the environment influence the way a person’s genes work, affecting genetic expression by “turning on and off” their genes.

- Multiple studies have shown that epigenetic changes – that is, chemical and behavioural markers – from trauma are passed onto offspring for at least two generations (in human beings) and up to six (in animals, such as mice).

- A feedback loop is hypothesised whereby epigenetic changes take place, but there is hope emerging from some studies that, with some treatments and in some environments, the loop can be interrupted, sparing future generations from experiencing the trauma-induced changes their parents endured.

Related articles: Assessing and Treating Trauma, Assessing and Treating PTSD, Case Study: Healing from Trauma as a Soldier.

References

- Curry, A. (2019). Parents’ emotional trauma may change their children’s biology. Science.org. Retrieved on 16 June 2024 from: https://www.science.org/content/article/parents-emotional-trauma-may-change-their-children-s-biology-studies-mice-show-how

- Erdelyi, K.M. (2022). Can trauma be passed down from one generation to the next? Health Central. Retrieved on 16 June 2024 from: https://www.healthcentral.com/condition/post-traumatic-stress-disorder/epigenetics-trauma

- Henriques, M. (2019). Can the legacy of trauma be passed down the generations? BBC. Retrieved on 16 June 2024 from: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190326-what-is-epigenetics

- Rozsa, M. (2023). Trauma seems to be passed down genetically – but experts still aren’t sure what that means. Salon.com. Retrieved on 16 June 2024 from: https://www.salon.com/2023/11/19/trauma-seems-to-be-passed-down-genetically–but-experts-still-arent-sure-what-that-means/

- Ryder, G. (2022). What is genetic trauma? Psych Central. Retrieved on 16 June 2024 from: https://psychcentral.com/health/genetic-trauma

- Valeii, K. (2024). How does intergenerational trauma work? Very Well Health. Retrieved on 12 June 2024 from: https://www.verywellhealth.com/intergenerational-trauma-5191638?print

- Yehuda, R. (2022). How parents’ trauma leaves biological traces in children. Scientific American. Retrieved on 16 June 2024 from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-parents-rsquo-trauma-leaves-biological-traces-in-children/