This second article in our three-part series on evidence-based practice explores the ‘Acquire’ step in the 5A model of EBP.

Read part one here.

Jump to section:

Introduction

In the first article in this series, we defined evidence-based practice (EBP) as:

“The integration of the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of client characteristics, culture, and preferences” (American Psychological Association, 2005).

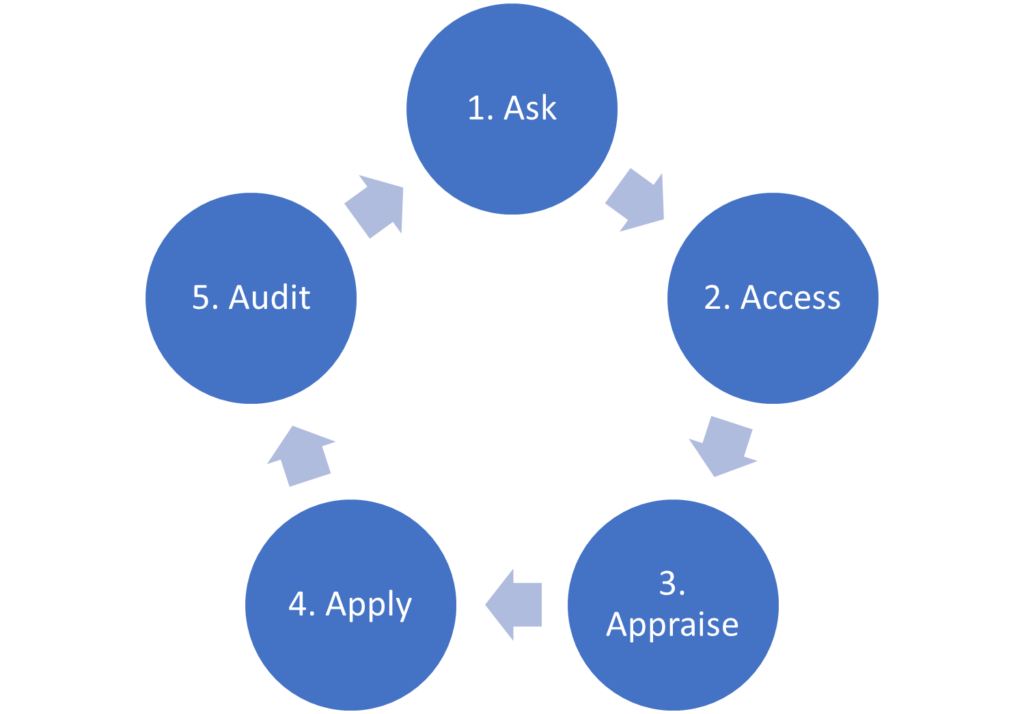

We also introduced the 5A model, a practical ‘how to’ (Figure 1). Step 1 involves asking a well-built clinical question using the PICO(TT) framework as a guide. In this article, we will focus on the second step of the process: accessing or acquiring the evidence.

Figure 1. The 5A’s model of EBP.

Acquiring the evidence requires an understanding of:

- Study designs and the questions each can best address

- Levels of evidence and where to search for each

- How to convert a PICO question into a search strategy

Study designs

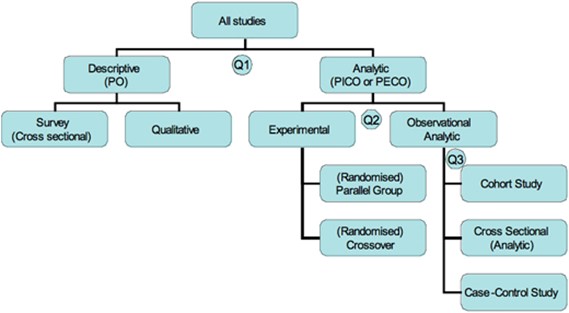

There are many clinical research designs. Figure 2 provides a flowchart of some of the decisions that lead to different study types.

Figure 2. Study designs (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, n.d.)

Question 1: What was the aim of the study?

Analytic studies, also known as inferential studies, aim to analyse the effect of an intervention (I) or exposure (E) on an outcome (O). This involves comparing the outcomes in the intervention or exposed group with the outcomes in a comparison or control (C) group.

By contrast, descriptive studies, also known as non-analytic studies, aim to describe one or more characteristics of a group. They do not try to establish or measure the relationship between variables such as the population (P) and outcome (O) (Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, n.d.). Descriptive studies include case reports and case series (not depicted in Figure 2), qualitative studies and survey (cross-sectional) studies. A case report describes outcomes for an individual patient. Because there is no control group for comparison, there is no statistical validity. When several case reports are described, this is known as a case series.

Question 2: If the study was analytic, did the researchers actively intervene or passively observe?

In experimental studies (also known as clinical trials), researchers actively manipulate variables to study cause-and-effect relationships. In other words, they allocate participants to an intervention group or control group. Interventions include particular types of therapy or screening assessments. Controls can be a placebo, standard care, or a comparison therapy or screening tool. If allocation to groups is done through randomisation and both participants and researchers are blinded to which group they are in, this randomised double-blind study design is very effective in controlling most of the biases that can occur in scientific research. For this reason, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the ‘gold standard’ in clinical research. RCTs are further categorised into parallel group designs and crossover designs based on whether participants serve as their own controls by alternating between the intervention and control (crossover design) or whether the intervention and control groups are separate (parallel design).

In contrast to experimental research, observational studies investigate associations or relationships between exposures and outcomes in real-world settings. In other words, researchers observe exposures that are already present in a population without intervening to manipulate them.

Question 3: When were the outcomes determined?

Observational research is further sub-divided into designs based on when the outcomes were determined relative to the exposure.

A prospective cohort study begins with the exposure and continues through a period of follow-up until the outcome. In this study design, patients who have a particular risk factor or receive a particular treatment are compared with another group who is not exposed to the risk factor or treatment being studied (Charles Sturt University, 2023). In a retrospective cohort study, the two groups to be studied are identified historically, that is, by going back in time to populations exposed to the risk factor or treatment. Cohort studies are less reliable than RCTs as the two groups being compared might differ in ways other than the variable being studied.

A case-control study begins with the outcome and traces back in time to the exposure. This type of study often relies on medical data or patient recall and is less reliable than an RCT or cohort study.

In a cross-sectional study (which may be analytic or descriptive), the outcome and exposure for a given population are measured simultaneously. This type of study is thus often referred to as a “snapshot” in time (Charles Sturt University, 2023).

Which studies best address the various types of clinical questions?

Not all study designs can answer every type of clinical question. Table 1 summarises appropriate study designs based on whether the clinical question relates to intervention/treatment, diagnosis/assessment, screening, aetiology or prognosis. Note: we will discuss systematic reviews and meta-analyses shortly.

Table 1. Matching the study design to the clinical question (Deakin University, 2023).

| Clinical Question | Appropriate Study Designs |

| Does this treatment work? (Intervention) | Systematic review or meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials Randomised controlled trial Prospective cohort study Case-control study Case series |

| How good is a diagnostic test? (Diagnosis) | Systematic review of cohort studies Prospective cohort study Case series |

| Should we screen? (Screening intervention) | Systematic review Randomised controlled trial Prospective cohort study Case-control study |

| What factors contribute to this disease? (Aetiology) | Systematic review of cohort studies Retrospective cohort study Case-control study Cross-sectional study Case series |

| How does this disease develop? (Prognosis) | Systematic review of cohort studies Prospective cohort study Retrospective cohort study Case Series |

Where to search? Start with the highest level of evidence

The definition of EBP refers to using the “best available evidence”. It’s now time to consider exactly what this means. There are two broad types of evidence in EBP: primary and secondary.

Primary evidence, also known as unfiltered evidence, consists of original individual studies, whether observational (case reports, case series, cross-sectional studies, case-control studies and cohort studies) or experimental (e.g., randomised controlled trials). Single studies provide the latest research findings, but the results may be inconsistent with other studies. It is therefore up to the reader to appraise the study and determine the relevance of the findings (Clinical Information Access Portal, n.d.). It is enormously time consuming and complex to locate, appraise and assimilate individual studies in order to make clinical decisions. Therefore, where secondary evidence exists, this should be the starting point for busy mental health professionals.

Secondary evidence, also known as filtered or pre-appraised evidence, provides an interpretation or analysis of primary studies on a particular topic. Secondary evidence includes systematic reviews, meta-analyses and evidence summaries. Secondary evidence is generated when experts select and appraise high quality studies, compile the findings and comment on their clinical relevance and implications (Clinical Information Access Portal, n.d.). Using secondary sources addresses the issues of limited time and EBP skills.

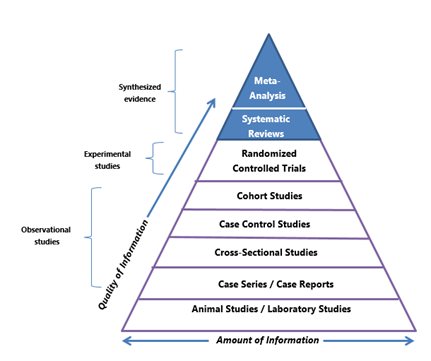

Hierarchies of evidence including the 6S pyramid

Various researchers have addressed the question of what constitutes the best evidence by organising evidence into levels. Figure 3 is a common example of a hierarchy of evidence that focuses primarily on the differences in the quality of individual studies, or primary evidence.

Figure 3. Hierarchy of evidence (Duke University Medical Center Library & Archives, 2023).

The hierarchy is shaped as a pyramid to convey that there are more studies of the designs shown at the bottom than the top. This means there are fewer experimental studies than observational studies. Observational research is generally considered a weaker form of evidence as it cannot establish cause-effect relationships. The strongest forms of evidence that appear at the peak are systematic reviews and meta-analyses, examples of synthesised, secondary or filtered evidence (more on these shortly).

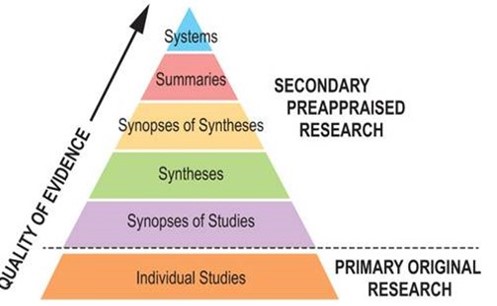

A more practical hierarchy of evidence for busy clinicians is the 6S pyramid (Figure 4) developed by one of the early pioneers of EBM, Brian Haynes and colleagues (DiCenso et al., 2009). The 6S pyramid arranges five sources of secondary evidence at the top of the pyramid, with the sixth ‘S’ comprising all of the individual studies that together constitute primary evidence. The idea is to start at the top of the pyramid and to work your way down until you find an answer to your clinical question. Using individual studies – that is, primary research – should be the last resort.

Figure 4. 6S Pyramid (Charles Sturt University, 2023).

Systems

At the top of the 6S pyramid are systems. These are computerised clinical decision support systems that provide guidance on management through linking individual client characteristics from an electronic medical record with the best available evidence. Although such systems are not yet in widespread use in psychological therapy settings, they do exist and have been the subject of evaluation (Lutz et al., 2022; Røst et al., 2020).

Summaries

The next level in the 6S pyramid, summaries, includes clinical practice guidelines and position statements. These evidence-based resources move from evidence to recommendations for managing patients. Evidence summaries synthesise high quality evidence from several sources lower in the pyramid, such as incorporating the findings from multiple systematic reviews.

One way to gauge the trustworthiness of Clinical Practice Guidelines is based on whether they use the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach when making recommendations. GRADE provides a transparent process for determining the certainty in the original evidence (also known as quality of evidence) and therefore the strength of recommendations (strong or weak/conditional).

Unfortunately, there are far fewer EBP resources designed for mental health professionals than EBM resources for medical professionals. However, many evidence summaries developed for doctors include relevant assessments and psychosocial interventions. Therefore, you may find content targeted at professionals such as psychologists, general practitioners or psychiatrists, or under broad headings such as mental health to be of value, irrespective of your profession or scope of practice.

A further point to make relates to access. Some EBP resources require a purchase or subscription. If you work in a large health service, you may have access to these resources. If not, many individual subscription rates are reasonable.

Point of care resources:

Clinical Practice Guidelines and Position Statements:

- Australian Psychological Society Clinical Psychologist Clinical Practice Guidelines

- American Psychological Association Clinical Practice Guidelines

- NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) Clinical Guidelines

- The Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) Clinical Guidelines

- RANZCP Position Statements

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners Mental Health Clinical Guidelines

- American Psychiatric Association Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Guidelines International Network (GIN)

- EBM Guidelines

Databases:

- Trip (turning research into practice) Database

- Epistemonikos

- ACCESSSS Smart Search

- JBI EBP Database

- PubMed and PubMed Clinical Queries

- Embase

- Cochrane Library

- Society of Clinical Psychology, Division 12 American Psychological Association

Synopses of syntheses

The next level down in the 6S pyramid is synopses of syntheses. This level represents synopses (summaries) of individual systematic reviews. Time-poor clinicians do not always have the time to review detailed systematic reviews in their entirety. The advantage of finding a synopsis is that it provides a short (usually 1 – 2 pages), structured summary. Synopses are often accompanied by a commentary that addresses the methodological quality of the systematic review and the clinical applicability of its findings (Clinical Information Access Portal, n.d.).

For example:

- Abstracts of systematic reviews indexed in APA PsycInfo

- Abstracts of systematic reviews indexed in MEDLINE (searchable via PubMed)

- Abstracts of systematic reviews indexed in Embase (an Elsevier database)

- Cochrane Clinical Answers (CCAs)

- Cochrane’s Plain Language Summaries (PLSs)

- Cochrane podcasts

Synthesis

The next lowest level is synthesis, which includes systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

A systematic review comprehensively evaluates existing primary evidence research to answer a clinical question regarding an intervention, diagnosis, screening, aetiology or prognosis. Unlike ad hoc approaches, systematic reviews tackle bias through explicit, systematic and predefined methods such as specifying a research question in advance (a priori), using a search strategy to locate all relevant research that is detailed enough it could be reproduced using the same methodology with the same results, having clear criteria for which studies will be included and excluded, and impartial and objective analytical approaches (Cochrane, 2022). By contrast, a narrative review (sometimes called a literature review) refers to a review conducted in a non-systematic way. Many journals no longer accept narrative reviews due to issues of bias.

During the preparation of a systematic review, researchers may combine the numerical results of all, or some, of the studies. This overall statistic, called a meta-analysis, summarises the effectiveness of an experimental intervention against a comparator intervention (Cochrane, 2022).

Syntheses can be located using the following websites and databases:

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses indexed in APA PsycInfo

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses indexed in MEDLINE (searchable via PubMed)

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses indexed in Embase (an Elsevier database)

- Nature Reviews Psychology (journal)

- Psychological Review (journal)

- Australian Psychological Society Evidence-based Psychological Interventions in the Treatment of Mental Disorders

Synopses of studies

Synopses of studies are summaries of individual, high quality clinical studies. Another way to think of this category is as critically-appraised journal articles.

Examples can be found using:

Single studies

The base of the 6S pyramid comprises individual studies which collect original (primary) data from patients. These studies are further arranged in the hierarchy shown in Figure 3.

Now that we are clear about the types and levels of evidence, it’s time to turn our attention to building a search strategy based on the clinical question to search these various forms of evidence.

Building a search strategy

A well-planned search strategy is essential for making efficient use of time. Without a strategy, searches return an unmanageable number of results, yield irrelevant references and miss key evidence.

Planning a search strategy involves:

- Identifying search terms

- Using truncation, wildcards and phrases

- Combining terms with Boolean Operators (AND, OR, or NOT)

- Applying limits to the search

Identifying search terms

The PICO question is the basis of the key concepts for the search. For each concept, keywords (synonyms and alternative spellings) and subject headings need to be identified.

Subject headings are a controlled and hierarchically-organised vocabulary used for indexing articles in particular databases. The MEDLINE database uses the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) thesaurus. The Embase database uses Emtree. PsycINFO uses the American Psychological Association index terms.

Let’s say the PICO question is “Can cognitive behavioural therapy improve self-esteem in clients with depression?”.

| P | I | C | O | |

| Concept | Depression | Cognitive behavioural therapy | No comparator | Self-esteem |

| Keywords (synonyms and alternative spellings) | Depressive disorderUnipolar depression | CBTCognitive behavioural therapy/iesCognitive psychotherapy | Self esteemSelf confidence | |

| MeSH term | Depressive disorder | Cognitive behavioural therapy | Self concept |

Truncation, wildcards and phrases

Truncation is used to capture words that share common roots. For example, depression and depressive share the root “depressi”. Different databases vary in which symbols are used for truncation, but they are commonly *, ? or $. Depressi* would detect both depression and depressive.

A wildcard (universal character) is a symbol that is used in place of one character, no character, or a group of characters. Again, databases vary in their rules for wildcard searching and in the symbols used. Wildcards are particularly helpful to detect plurals and alternate spellings. For example, behavio?r will capture both US and British spellings and patient* will return results for patient and patients.

To search for a phrase rather than a keyword, double inverted commas can be used e.g., “cognitive psychotherapy”.

Combining terms with Boolean operators

Boolean Operators are used to combine concepts or keywords to improve the chances of finding relevant information. The most commonly used Boolean Operators are AND, OR, and NOT. Brackets (parentheses) define the order in which the concepts are processed.

- Using AND narrows the search and decreases the number of results.

- Using OR searches a broader range of keywords and increases the number of results.

- Using NOT excludes information not required and reduces the number of results.

Returning to the example above, one search strategy using Boolean operators would be:

(Depression OR “depressive disorder” OR “unipolar depression”) AND (“cognitive behavio* therap*” OR CBT OR “cognitive psychotherapy”) AND (self-esteem OR “self esteem” OR “self confidence” OR “self concept”).

Applying limits to the search

Limits can be used to further refine a search strategy or filter results. The features vary depending on the source but can include:

- Language

- Date of publication

- Type of study e.g., systematic review, meta-analysis, randomised control trial, cohort study, etc

- Gender

- Age group

We have now completed Step 2 of the 5A’s process: Acquire the evidence. In the final article in this series, we will describe the remaining steps of the 5A process: Appraise, Apply and Audit.

Key takeaways

- The second step in the 5A process of evidence-based practice involves searching for evidence.

- Study designs can be experimental, such as randomised controlled trials, or observational, such as cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, case series and case reports. Experimental designs are stronger as they can determine cause-and-effect relationships.

- Different study designs address different clinical questions.

- Evidence can be categorised into levels with the most synthesised, filtered forms representing the highest level and descriptive individual studies representing the lowest level.

- Wherever possible, busy mental health professionals should seek secondary evidence that is pre-appraised such as clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

- Where there are gaps in the evidence base, randomised controlled trials that meet methodological standards for validity, impact and clinical relevance can be used. However, individual studies (primary evidence) are weaker forms of evidence than secondary evidence and are more challenging to incorporate into routine clinical practice.

- Using a search strategy based on a PICO clinical question is a more efficient way to access the evidence base and more likely to yield a manageable number of relevant results.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2005). Policy Statement on Evidence-Based Practice in Psychology. https://www.apa.org/practice/guidelines/evidence-based-statement

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. (n.d.). Study designs. University of Oxford. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/ebm-tools/study-designs

- Charles Sturt University. (2023). Evidence-Based Practice: Levels of Evidence. https://libguides.csu.edu.au/ebp/levels

- Clinical Information Access Portal. (n.d.). EBP Learning Modules. NSW Health. https://www.ciap.health.nsw.gov.au/training/ebp-learning-modules/

- Cochrane. (2022). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022) (J. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li , M. Page, & V. Welch, Eds.). https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Deakin University. (2023). Quantitative study designs. https://deakin.libguides.com/quantitative-study-designs

- DiCenso, A., Bayley, L., & Haynes, R. B. (2009). ACP Journal Club. Editorial: Accessing preappraised evidence: fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model. Ann Intern Med, 151(6), Jc3-2, jc3-3. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-6-200909150-02002

- Duke University Medical Center Library & Archives. (2023). Evidence-Based Practice: Study Design. https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/ebm/studydesign

- Lutz, W., Deisenhofer, A. K., Rubel, J., Bennemann, B., Giesemann, J., Poster, K., & Schwartz, B. (2022). Prospective evaluation of a clinical decision support system in psychological therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol, 90(1), 90-106. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000642

- Røst, T. B., Clausen, C., Nytrø, Ø., Koposov, R., Leventhal, B., Westbye, O. S., Bakken, V., Flygel, L. H. K., Koochakpour, K., & Skokauskas, N. (2020). Local, Early, and Precise: Designing a Clinical Decision Support System for Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services. Front Psychiatry, 11, 564205. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.564205