This final article in our three-part series explores the ‘Appraise’, Apply’ and ‘Assess’ steps in the 5A model and addresses some of the limitations of EBP in psychotherapy.

Read part one here, and part two here.

Jump to section:

Introduction

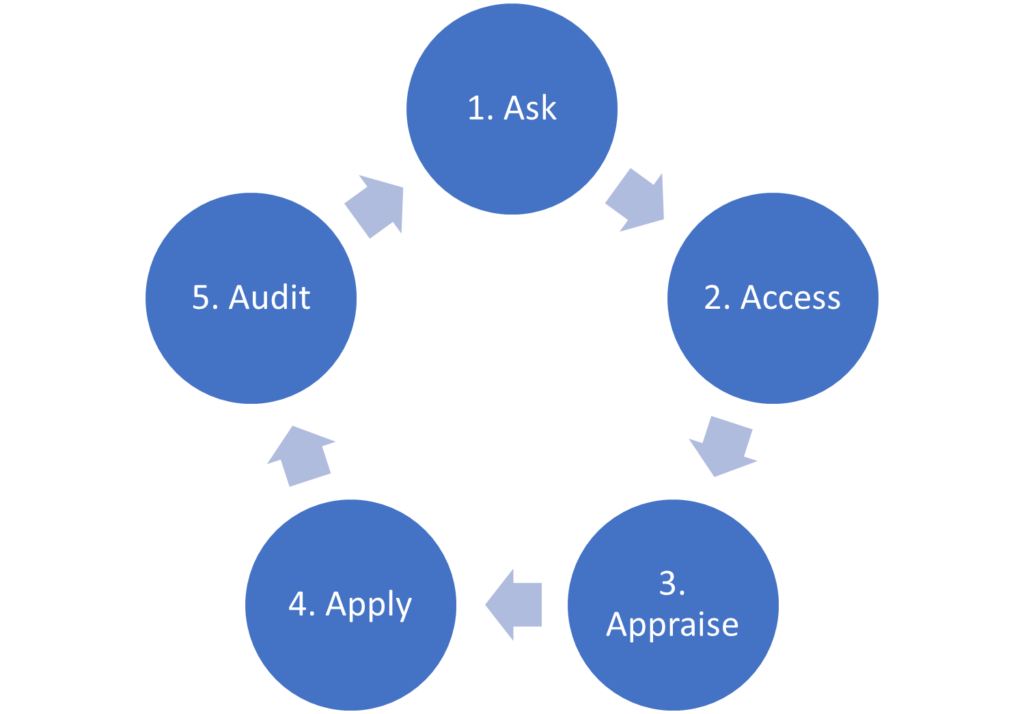

In the first article in this series, we introduced the 5A model and explained Step 1: (How to) Ask a well-built clinical question using the PICO framework. In the second article, we covered Step 2: Access the evidence. In this final article of the series, we will explore the remaining steps in the process, Step 3: Appraise, Step 4: Apply and Step 5: Audit. We will also consider some of the limitations of EBP in psychotherapy.

Figure 1. The 5A’s model of EBP.

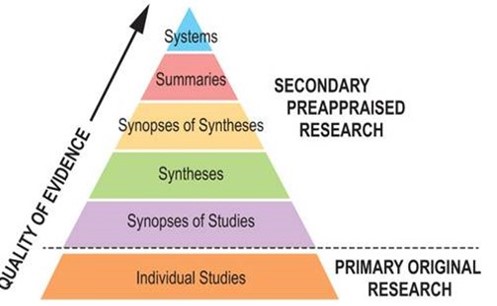

Recall that a practical hierarchy of evidence for busy mental health professionals is the 6S pyramid (Figure 2) (DiCenso et al., 2009). The 6S pyramid arranges five sources of secondary evidence at the top of the pyramid, with the sixth ‘S’ comprising all of the individual studies that together constitute primary evidence.

Figure 2. 6S Pyramid (Charles Sturt University, 2023).

Step 3: Appraise the evidence

If secondary evidence, such as a clinical practice guideline, systematic review or meta-analysis, that answers the clinical question and is from a reliable source has been identified, the process of critical appraisal does not need to be undertaken. Reliable sources only publish evidence that meet certain standards in terms of methodological quality. Trustworthy clinical practice guidelines use the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the original evidence, and base the strength of recommendations (strong or weak/conditional) on this certainty. The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM) at The University of Oxford has produced a checklist for appraising systematic reviews. Another checklist has been produced by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). These checklists evaluate the evidence for validity, impact of results and clinical relevance.

If only one or two individual studies (primary evidence) have been identified, it is necessary to evaluate the research design, sample size, methodology, and statistical analysis of each study to determine its credibility and applicability to the clinical question (Guyatt et al., 2008). It’s important to remember that not all evidence is of the same quality. By appraising the evidence, clinicians can identify the most robust and reliable information to guide decision-making.

It takes time, specialist training and practice to learn how to critically appraise primary evidence. For further information about how to critically appraise a randomised controlled trial, refer to this checklist from CEBM, or this checklist from CASP.

Step 4: Apply the evidence

Recall that EBP combines the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of client characteristics, culture and preferences. Step 1 (Ask), Step 2 (Acquire) and Step 3 (Appraise) in the 5A model all deal with the best available evidence.

Step 4 (Apply the evidence) involves determining how the best available evidence applies to the specific patient that was the subject of the original clinical question, taking into account your own clinical expertise and the client’s characteristics, culture and preferences. This is sometimes referred to as determining the external validity or generalisability of the research results and may be carried out as part of Step 3 (Appraise) (Glasziou et al., 2009).

It is unlikely there will be a perfect match between the best available evidence and the PICO question, so judgment is required to decide if the match is close enough to assist with your clinical decision making.

Some questions to consider are:

- Is my client similar enough to the patient population in the evidence-based resource (whether that is a clinical guideline, systematic review, meta-analysis or RCT)?

- Is this assessment method or intervention feasible in my setting? Are there any barriers to implementation?

- Will the potential benefits outweigh the potential harms and costs?

- What are the alternatives?

- What is important to my client?

The integration of evidence into clinical practice involves a shared decision-making process, where you as the mental health professional and the client collaborate to select the course of action.

Step 5: Audit/assess the effects

EBP is a process intended for mental health professionals to incorporate into their routine clinical practice. Thus, it is important that you learn to do it as efficiently as possible. The last step of evidence-based practice (EBP), Audit or Assess, involves self-evaluation regarding the EBP process.

EBP also encourages ongoing evaluation and monitoring of treatment outcomes to ensure the effectiveness of interventions for clients. Where possible, outcome measures and standardised assessment tools are used to track progress and adjust treatment strategies accordingly. Applying a systematic approach helps identify which interventions are most beneficial for specific populations and facilitates continuous improvement in practice.

Self-reflective questions include (Glasziou et al., 2009; Hoffman et al., 2017):

- Did I ask a well-formulated clinical question?

- Did I consider the best sources of evidence for the type of clinical question?

- Did I search the databases efficiently?

- Did I use the hierarchies of evidence as my guide for the type of evidence that I should be searching for?

- Where possible, did I search for and use information that is higher up in the pyramid, for example, summaries and syntheses?

- Can I clearly explain what the evidence means to my patients and involve them in shared decision making where appropriate?

- Did I integrate the critical appraisal into my clinical practice?

- Did the application of new evidence create the desired outcome for my patient?

- Should this new information and/or clinical practice procedure continue to be incorporated into my day-to-day practice?

- Am I proactively monitoring emerging evidence in my field?

The University of Canberra has produced a comprehensive self-evaluation checklist that may be useful to print.

Limitations of evidence-based practice in psychotherapy

While evidence-based practice (EBP) has numerous benefits, it is important to acknowledge its limitations in the context of psychotherapy. Understanding these limitations will help you navigate the complexities of incorporating evidence into your practice more effectively.

- Individual Differences: EBP often relies on group-level research findings which may not fully account for the unique characteristics and needs of individual clients. Psychotherapy is a highly personalised endeavour and factors such as cultural background, personal history, and preferences can influence treatment outcomes. Applying generalised evidence to diverse individuals may overlook important nuances and limit the effectiveness of interventions.

- Mental Health is Complex: Mental health issues are complex and multifaceted, making it challenging to capture their full scope within the confines of controlled research studies. The reductionist nature of EBP may overlook the intricacies of individual experiences, including comorbidities, developmental factors, and the interplay between psychological, social, and biological factors. Psychotherapists need to be aware of the limitations of research in addressing the full complexity of mental health issues.

- Research Gaps and Lag: EBP heavily relies on the availability of high-quality research. However, there are often gaps in the evidence base, especially in emerging or specialised areas of psychotherapy. Additionally, research may lag behind current practices, leaving psychotherapists to rely on clinical expertise and judgment when evidence is scarce or outdated. Treatments lacking sufficient evidence may still be cautiously used in line with clinical expertise and patient preferences.

- Some Types of Therapy Are Easier to Study Than Others: EBP has greatly enhanced the field of psychotherapy by advocating for treatments grounded in empirical research. However, EBP’s applicability faces challenges when it comes to certain forms of psychotherapy, such as those that are more nuanced and less amenable to RCTs, unlike Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). The limitations of EBP in this context emerge from the complex and individualised nature of therapies like psychodynamic or humanistic approaches, which emphasise the therapeutic relationship and subjective experiences. These therapies often involve personal dynamics that are difficult to capture in the controlled settings of RCTs where standardisation is crucial. Additionally, the reliance on manualisation and protocols in RCTs might undermine the authenticity and spontaneity required in some psychotherapeutic modalities, potentially leading to an oversimplification of the therapy process. Thus, while EBP has revolutionised the validation of treatments like CBT, it faces inherent constraints in capturing the rich diversity of psychotherapeutic approaches.

- Intervention vs Common Factors: While EBP emphasises specific treatment protocols, research increasingly acknowledges that the effectiveness of therapy is influenced not only by the chosen modality but also by shared elements such as the therapeutic relationship, client factors, and contextual variables. These common factors, including empathy, rapport, and client motivation, play a substantial role in shaping therapeutic outcomes. However, EBP’s focus on manualised interventions and standardised measures might inadvertently downplay the importance of these common factors. Thus, while EBP offers a valuable framework for evaluating treatment efficacy, it must contend with the challenge of incorporating and accounting for the dynamic and often intangible elements that contribute significantly to the success of psychotherapy.

- Ethical Considerations: EBP places an emphasis on using interventions with proven efficacy. However, this can create ethical dilemmas when evidence supports certain treatments but client preferences or values differ. Psychotherapists must navigate the tension between evidence-based recommendations and respecting client autonomy, cultural considerations, and personal preferences.

- Funding and Resource Limitations: Implementing EBP requires resources, including access to research literature, training in critical appraisal, and time to stay up-to-date with the latest evidence. These resources may not be readily available to all psychotherapists, particularly those in resource-limited settings or with limited institutional support. The practical challenges of accessing and applying evidence can hinder the widespread adoption of EBP.

- Publication Bias and Selective Reporting: The publication of research studies is subject to publication bias, where studies with significant or positive findings are more likely to be published, while those with null or nonsignificant results may remain unpublished. This can skew the evidence base and lead to an overemphasis on certain interventions or outcomes, potentially misleading psychotherapists.

- Contextual Factors: EBP often focuses on treatment outcomes in controlled settings, which may not fully reflect real-world clinical practice..

Acknowledging these limitations does not diminish the value of EBP but highlights the need for a nuanced and integrative approach. Mental health professionals should balance evidence with clinical expertise, client preferences, and ethical considerations. Engaging in ongoing professional development, fostering a reflective practice, and considering the broader context of the individual’s treatment can help address the limitations of EBP and provide comprehensive and tailored care to clients.

Key takeaways

- Evidence-based practice (EBP) involves integrating the best available research evidence with clinical expertise and client values to inform clinical decision-making.

- The 5A process of evidence-based practice includes formulating a clinical question, searching for evidence, critical appraisal, integrating evidence with clinical expertise and client factors, and assessing outcomes.

- Because the quality of research evidence varies, critical appraisal based on validity, clinical impact, and applicability is required.

- Wherever possible, mental health professionals should use clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews and meta-analyses as these forms of secondary evidence are pre-appraised.

- Applying the evidence involves a shared decision-making process in which the client’s characteristics, culture and preferences are considered.

- Applying the evidence also involves clinical expertise as it is unlikely there will be a perfect match between the best available evidence and the PICO question.

- The final step in the 5A model, audit, involves self-evaluation and monitoring of treatment outcomes to ensure the effectiveness of interventions for clients.

References

- Charles Sturt University. (2023). Evidence-Based Practice: Levels of Evidence. https://libguides.csu.edu.au/ebp/levels

- DiCenso, A., Bayley, L., & Haynes, R. B. (2009). ACP Journal Club. Editorial: Accessing preappraised evidence: fine-tuning the 5S model into a 6S model. Ann Intern Med, 151(6), Jc3-2, jc3-3. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-6-200909150-02002

- Glasziou, P., Del Mar, C., & Salisbury, J. (2009). Evidence-based practice workbook: Bridging the gap between health care research and practice (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing.

- Hoffman, T., Bennett, S., & Del Mar, C. (2017). Evidence-Based Practice Across the Health Professions (3rd ed.). Elsevier.