Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is widely held to be best treated through early diagnosis and treatment, but new findings question that traditional wisdom.

Jump to section:

Introduction

The mental health community has long believed that the best outcomes for children and adolescents with ADHD is to receive early diagnosis and treatment, but a new study offers a controversial view. We consider both positions given questions over the accuracy of available screening tools and the changing landscape of both diagnoses and prescribed medications.

Recommended reading related to this topic:

- Neurodiversity, Neurodivergence and Being Neurotypical

- ADHD vs Neurotypical Brains: Implications for Therapists

- Harnessing ADHD Benefits with a Neurodivergent-affirmative Approach

- Comorbidities in Child ADHD

Screening/diagnostic problems with the instruments

The Australian ADHD Professionals Association (AADPA) summarises the results of a recent systematic review, noting that none of the current diagnostic tools for ADHD are acceptable. The researchers’ metanalysis found that:

“Current screening tools for children and adolescents do not meet acceptable sensitivity and specificity rates for universal screening. While ADHD is likely underdiagnosed and undertreated in Australia, there is a lack of accurate ADHD screening tools to enable cost-effective population-based screening in children and adolescents (AADPA, 2023).

ADHD: More prescriptions; is it increasing?

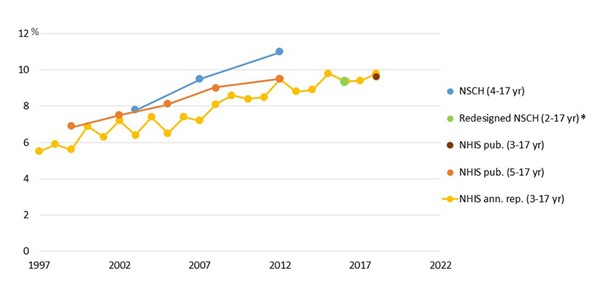

Not only are we uncertain of the value of current assessments, but also it appears to some observers that ADHD is on the rise. Certainly, the number of prescribed medications for it has doubled in the last two decades (even though, as noted above, some ADHD experts, such as the AADPA, insist that it is still underdiagnosed). The Centers for Disease Control in the United States have graphed an upward trend in ADHD diagnosis throughout recent years. The CDC says:

“The percent of children estimated to have ADHD has changed over time and its measurement can vary. The first national survey that asked parents about ADHD was completed in 1997. Since that time, there has been an upward trend in national estimates of parent-reported ADHD diagnoses across different surveys, using different age ranges. It is not possible to tell whether this increase represents a change in the number of children who have ADHD, or a change in the number of children who were diagnosed” (CDC, 2022).

Their graph of ADHD diagnosis is from published nationally representative survey data (See figure below).

Figure: ADHD diagnosis throughout the years.

(Percent of children with a parent-reported ADHD diagnosis)

(CDC, 2022)

Upswing in prescriptions for ADHD medication

Louise Kazda, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Sydney, conducted research with colleagues at University of Sydney and Bond University, and found that increasing awareness of ADHD has led to consistent rises in the number of children diagnosed with and treated for it, both internationally and in Australia (Kazda, 2021), with diagnoses nearly doubling since 1997 (CDC, 2022; see figure, above).

So, we come to the million-dollar question: if there is a higher incidence of ADHD (at least according to the parents surveyed) and there are twice as many prescriptions as several decades ago, shall we continue to hold to the professional view that we should seek early diagnosis and treatment if we want the best outcomes? Let’s see both sides of the argument.

Early diagnosis and treatment: Better outcomes, or not?

Traditional wisdom proclaims that early diagnosis is generally beneficial.

Mayo Clinic: It’s helpful

Mayo Clinic, for example, notes that early diagnosis and treatment can help attain better outcomes because children with ADHD:

- Often struggle in the classroom, leading to academic failure and negative judgments by other children, parents, and teachers

- Tend to have poor self-esteem

- Tend to have more accidents and injuries of all kinds than children without ADHD

- Are more likely to have trouble interacting with, and thus being accepted by, peers and adults

- Are at increased risk of alcohol and drug abuse and delinquent behaviour (Mayo Clinic, 2019).

ADHD Australia: Poor sense of self and failure without treatment

ADHD Australia, meanwhile, observes that without appropriate diagnosis, treatment, and support, children with ADHD may – through experiencing the above issues – “constantly find themselves on the receiving end of disciplinary, academic and social repercussions” which is likely to result in “a poor sense of self”, a sense of being “a failure” (including predicting future failure), and enhance the likelihood of developing oppositional and defiant behaviour. Such children show an increased probability of developing anti-social behaviour, anxiety, and depression, alcohol and substance abuse issues and eating disorders in adulthood, as well as “adverse long-term health outcomes which can reduce life expectancy”. As adults, those with ADHD are at higher risk of work, financial, and relational difficulties, and of divorce or relational breakdown, driving infringements, criminality, injury, self-harm, and suicide (ADHD Australia, 2019).

Alpha Psychiatry: Early-diagnosed adolescents liked themselves more

Looking specifically at the social domain relative to time of diagnosis, a study cited in Alpha Psychiatry compared two groups of adolescents with regard to self-esteem and loneliness. One group was comprised of 55 adolescents who had received an early diagnosis (between 6 and 8 years of age), were treated regularly, and were followed up for six years. The other group was 62 adolescents who had been diagnosed late (between 12 and 14). Results showed that the early-diagnosis adolescents had higher scores on the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale, and lower scores on the UCLA Loneliness Scale. The results did not change with regard to ADHD subtypes or gender; thus, the researchers concluded that the late-diagnosed adolescents with ADHD felt more alone than the early-diagnosed adolescents and liked themselves less compared to the early-diagnosed group (Zahmacioglu & Kilic, 2017).

ADHD Australia, too, concludes that in order to reduce the risks associated with having ADHD and to improve outcomes, it is “vital” that children receive an appropriate early diagnosis as well as evidence-based treatment and support, which may include medication and also “scaffolding support” to help bridge the gap between the self-control capacity that the children have and the expectations placed upon them at home and at school, so that they can feel good about themselves, and achieve success (ADHD Australia, 2019).

Kazda et al: A contradictory finding

Notwithstanding the prevailing view that early diagnosis and treatment is better for children with ADHD, at least one recent study’s findings would seem to question this. Specifically, researchers in the Kazda et al study (2021) asked whether the increase in diagnoses could be stemming from an “over-medicalisation” of everyday experiences that are part of the human condition. Moreover, they wondered, may there be more diagnoses now because awareness of ADHD has increased, and detection methods have improved? If, the researchers said, either or both of these conditions obtained – especially given the lack of accurate assessment tools – the higher numbers of “diagnoses” might include many incorrect (“false positive”) ones, or ones which would not have met previous thresholds, with negative downstream consequences in the treatment thereof.

“Frustrating” but “normal”

Kazda’s research, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA (Kazda et al, 2021), claims that the large uptick in diagnoses may be largely due to children whose behaviours fall within a “normal” but “frustrating” range (so, seeming to support the “over-medicalisation” view). Such children, the study concluded, are unlikely to benefit from a diagnosis and may be harmed by it. This surge in diagnoses, said the researchers, also results in limited resources being stretched thinner among more children, ultimately taking away from those with severe problems who would benefit from more support.

The study reviewed the results from more than 300 studies on ADHD over the past 40 years to determine which children are being newly diagnosed and if they benefit. Summarising a huge variety of studies in a way not done before, Kazda and colleagues found the following:

- Since the 1980s, increasing numbers of school-aged children and adolescents around the world have been diagnosed with ADHD and medicated for it.

- Ways of diagnosing ADHD also vary between countries and change over time, with criteria generally becoming less stringent. This ensures many potentially new cases could be discovered, depending on how low the bar is set (so, supporting the increased awareness/detection hypothesis). Almost half of all children diagnosed with ADHD in the U.S., for example, have mild symptoms, with only 15% presenting with severe symptoms. Only 1% of children in an Italian study had severe ADHD-related behaviour.

- A study in Sweden showed that, while diagnoses increased more than five-fold over 10 years, there was no increase in clinical ADHD symptoms over the same time, meaning that with the lowering of the diagnostic bar, Swedish children diagnosed with ADHD are, on average, less impaired and more similar to those without an ADHD diagnosis.

Different cost/benefit ratio for mild and severe symptoms

The study authors divided their conclusions between children with mild symptoms and those with more severe symptoms. For children with mild symptoms, the families incur substantial costs as well as potential harms because:

- Gaining an ADHD label can mean social and psychological stigma that overrides any support offered, generating negative effects in these and academic domains that non-ADHD children do not experience.

- Medication reduces symptoms to a lesser extent in children with mild ADHD than those with severe symptoms.

- Medication for mild symptoms has potential negative effects on academic outcomes compared to unmedicated children with similar behaviour.

- Medication doesn’t reduce the risks of injuries, criminal behaviour and social impairment as much as it does for those with severe symptoms.

For children with severe symptoms, the medication may help much more, but the ever-increasing rates of diagnosis mean that schools and other public institutions now must divide the “pie” of funding between many more students and are struggling to give support to every child diagnosed, meaning that the most severe cases may be left behind.

For Kazda and associates, the operative phrase from their research is “correct diagnosis”. They recommend a stepped-diagnosis approach, in which the most severe cases would be diagnosed swiftly and efficiently. For the milder cases, parents and teachers could take a “wait and see” approach, meaning that ultimately, many won’t need to be labelled or treated (Kazda, 2021).

The Kazda study is an eye-opener, and we can sensibly keep its findings in mind. Even beyond all that we have discussed in this article, there is the complicating factor of the many comorbidities that accompany ADHD. We examine this in another article.

ADHD courses and training

With ADHD being one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders, it is crucial for therapists to be well-trained in its nuances. Following are some ADHD courses and training that you may be interested in:

- Working with ADHD in Children and Adolescents

- Working with ADHD in Adults

- OnTrac: A CBT Based Manualised Group Program for Adolescents with ADHD

Note: These courses are accessible (on-demand) through Mental Health Academy membership. If you are not currently a member, click here to learn more and join.

Key takeaways

- The prevailing view of ADHD is that it is best diagnosed and treated early in a child’s life, but respected ADHD experts have shown that the current diagnostic and screening tools are inaccurate.

- There are many more parent-reported cases of ADHD and double the number of prescriptions for it as there were two decades ago, but these realities may be due in large part to both pathologising normal but frustrating child behaviour and to the bar being lowered for what is considered to be sufficient severity for diagnosis.

- The increase in diagnoses may result in more harm than good, especially for the majority of cases of ADHD, which are mild.

References

- ADHD Australia. (2019). ADHD in Children. ADHD Australia. Retrieved from: ADHD in Children 201909 factsheet – Version 1.4.

- Australian ADHD Professionals Association (AADPA). (2023). ADHD Screening and identification. aadpa.com.au. Retrieved on 13 July, 2023, from: https://adhdguideline.aadpa.com.au/identification/screening-and-identification/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. CDC. Retrieved on 13 July, 2023, from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/timeline.html

- Kazda, L. (2021). Child ADHD is on the rise, but many of these diagnoses may be unnecessary or harmful. ABC: The Conversation. Retrieved on 13 July, 2023, from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-04-13/adhd-rising-children-borderline-cases-value-of-diagnosis/100064168

- Kazda, L, Bell, K, Thomas, R, McGeechan, K, Sims, R, & Barratt A. Overdiagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Scoping Review. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4): e215335. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5335

- Mayo Clinic. (2019). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved on 31 May, 2023, from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/adhd/symptoms-causes/syc-20350889

- Zahmacioglu, O. & Kilic, E. (2017). Early diagnosis and treatment of ADHD are important for a secure transition to adolescence). Alpha Psychiatry, (18)1, 2017. Retrieved on 18 July, 2023, from: https://alpha-psychiatry.com/en/early-diagnosis-and-treatment-of-adhd-are-important-for-a-secure-transition-to-adolescence-131618