Research shows that psychedelics alone are not effective treatments for mental illness – the therapist plays a critical role. This article explores why.

Jump to section:

Introduction

Psychedelic-assisted therapies (PATs) use hallucinogenic substances that produce non-ordinary states of consciousness, like psilocybin and MDMA, in conjunction with psychotherapy to treat mental illness. The past two decades have been described as a ‘renaissance’ as scientific research that was halted in the 1970s has resumed and gathered momentum (George et al., 2022; McClure-Begley & Roth, 2022; Nutt, 2019).

In the previous article of this series, we discussed:

- The urgent need for more effective therapies to treat mental illness

- The classes of hallucinogens such as psychedelics (which include psilocybin) and empathogens/entactogens (which include MDMA)

- Terminology i.e., the fact that the term ‘psychedelic’-assisted therapies includes the use of hallucinogens that are not technically psychedelics

- The history of psychedelic research, and

- Various clinical trials showing evidence for the use of psilocybin in the treatment of mood disorders and alcohol dependence.

In this article we will take a closer look at the therapy component of PAT, consider how PAT works by exploring psychological and neurobiological mechanisms, and finish with the legal status of psychedelic-assisted therapies across the globe.

The ‘P’ vs ‘T’ of Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies (PAT)

If the effects of hallucinogens were due solely to their pharmacology, we would expect people to have broadly similar responses to the same dose of the same drug. However, this is not what was observed for hallucinogenic drugs in clinical and research contexts during the pre-prohibition years (Metzner & Leary, 1967). Nor does this appear to be the case for recreational usage (McElrath & McEvoy, 2002; Shewan et al., 2000). It turns out that the effects are highly subjective and can vary significantly between users across societies, cultures and subcultures (Wallace, 1959).

Thus, the role of what have been called “nondrug parameters of psychopharmacology” or “extra-pharmacological parameters” has been debated extensively over the past century (Hartogsohn, 2017). The set and setting hypothesis is an enduring extra-pharmacological concept popularised by Timothy Leary (Hartogsohn, 2017; Winkelman, 2021). Leary is the controversial Harvard psychologist best known for his role in the American counterculture movement of 1960s during which he encouraged young people to “turn on, tune in, and drop out” (Nichols, 2016). Leary argued that set and setting are the most important determinants of the psychedelic experience, and can be used to ‘program’ desirable outcomes such as a religious experience (Leary, 1964, 1970; Leary et al., 1963; Metzner & Leary, 1967). This context dependence is consistent with the traditional shamanic and spiritual uses of psychedelics and has been confirmed in more contemporary research (Australian Psychological Society, 2021; Carhart-Harris et al., 2018).

So, what exactly are set and setting? Set refers to the mindset or internal state of the user, including their personality, preparation for the experience, intention, mood, expectations, fears and wishes. Setting refers to the environment in which the medicine session or “journey” occurs, including the physical space, the emotional environment (such as music), and the cultural environment (the societal ideas that influence the users’ beliefs about the drug and the world in general) (Hartogsohn, 2017; Kelly et al., 2023; Leary, 1966; Metzner & Leary, 1967). Another important contextual or environmental influence are the therapists or guides, and their ability to develop a trust-based therapeutic relationship (Australian Psychological Society, 2021; Kelly et al., 2023; Reiff et al., 2020).

The ‘T’: set and setting model

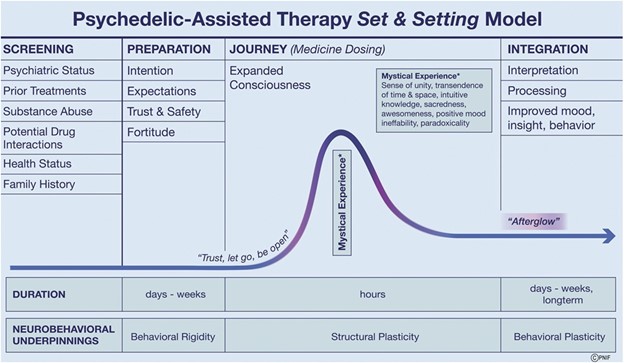

Because the evidence indicates psychedelics have a context-dependent effect, it would be unethical to conduct clinical trials involving administration of the drug alone. A supportive environment, that is, a comfortable setting and suitably trained psychotherapists, psychologists, counsellors or psychiatrists, is essential (Rucker et al., 2018). Therefore, the set and setting model (Figure 1), designed to achieve a “transformative yet safe patient experience”, is currently used in all PAT clinical trials (Kelly et al., 2023). However, it is important to note that there is no universal protocol (Browne, 2023).

Figure 1. Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy Set and Setting Model (Kelly et al., 2023).

PAT paradigms typically involve the following stages (Andersen et al., 2021; Australian Psychological Society, 2021; Kaelen et al., 2015; Passie, 2018; Rucker et al., 2018; Tai et al., 2021):

- Screening for appropriateness of participation. High-risk individuals such as those with a personal or family history of psychosis, personal history of mania, violence towards others, acute suicidality, serious cardiovascular, renal, liver or neurological comorbidity, current or expected pregnancy are typically excluded.

- Preparatory therapy involving one or more psychological counselling sessions in the days or weeks prior to the active medicine session(s). Preparatory therapy allows the therapists to discover the client’s history and intentions and to educate them about what to expect of the medicine session(s), including the possibility that long forgotten, unknown or emotionally charged material may surface. A mantra often encouraged is “trust, let go, be open.” Preparation also focuses on establishing the therapeutic alliance between the therapists and participants.

- Psychedelic active session(s) “(journey”/medicine dosing). Unlike traditional psychopharmacology such as treatment with antidepressant medication, PAT generallyinvolves only one or two dosing sessions of the psychedelic drug. Highly restricted scheduling (depending on the jurisdiction) generally requires the drug to be administered by or under the supervision of a psychiatrist who can also medically monitor the treatment. The client needs to be accompanied at all times, preferably by the therapist(s) who provided the preparatory therapy. A male-female therapist dyad is deemed necessary due to reports of sexual abuse during MDMA-assisted therapy. Onset of the drug effect takes around 30 mins, peaks after about 90 mins and subsides after 4 – 6 hours. The journey takes place in a comfortable room with appropriate art and lighting, with the client reclining on a bed or sofa with eyeshades. New age or classical music is often used as it enhances the emotional response to psychedelics. This session may be challenging as dysphoria, confusion, anxiety, agitation, panic and paranoia occur in a proportion of psychedelic experiences. Such reactions are usually mild and respond to reassurance and attendance to physical pain or discomfort. The typical psychotherapeutic approach is non-directive, supportive psychedelic or psycholytic therapy that facilitates rather than directs the experience. In many active sessions, the client will have what is termed a mystical experience.

- Integration therapy session(s). These are arguably the most important therapeutic stage of PAT and involve interpretation of the material that emerged during the active session(s) and integration of these experiences for long-term positive change to outlook and behaviour. Researchers currently argue that it is unclear whether it is the psychedelic drug itself, the psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy experience, or drug-facilitated enhancements in the therapeutic alliance that promote such change (Garcia-Romeu & Richards, 2018). The first integration session occurs the day after the journey, in the so-called “afterglow” period, followed by subsequent sessions over weeks.

The role of the therapist

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the equivalent body in Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), acknowledge that the close involvement of therapists is critical for the success of PAT. The FDA requires that two trained therapists are present for active sessions, and that they:

- Are mental health care practitioners with a professional license in good standing

- Have demonstrable clinical psychotherapy or mental health counselling experience, and

- A Masters’ level qualification (Tai et al., 2021).

How do psychedelic-assisted therapies work?

Psychedelics likely work by disrupting activity in brain networks that encode habits of thoughts and behaviour (Sarris et al., 2022). There is evidence that psychedelics induce neuroplasticity after both single and repeated administration, and that these cellular and molecular changes drive the long term changes in beliefs and behaviours associated with successful treatment of mental health conditions (Carhart-Harris & Friston, 2019; de Vos et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2023; Nichols, 2016; Vargas et al., 2023).

Legal status

Currently (as of June 2023), psychedelic substances are illegal outside designated clinical research trials in most jurisdictions. Jamaica and Costa Rica are two notable exceptions (Ducharme, 2023).

In the United States the FDA has granted breakthrough therapy status to MDMA and psilocybin putting these drugs on a federal regulatory fast track to approval. There are signs that this may happen soon, with a published letter from the US Department of Health and Human Services indicating they anticipate the FDA will approve MDMA by 2024 (Reardon, 2023). In 2020, the state of Oregon voted to legalise psilocybin for therapeutic use, and in 2022 Colorado voted to decriminalise psilocybin, DMT, ibogaine and mescaline (Ducharme, 2023; Law, 2022).

The FDA has also allowed a limited number of people to use MDMA under the expanded access program designed for patients with serious or life-threatening conditions who are unable to participate in clinical trials (Ducharme, 2023; Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, n.d.). Regulators in other jurisdictions such as Switzerland, Canada and Israel have made similar decisions to allow special access for patients with severe conditions (Argento et al., 2021).

From 1 July 2023, Australia will be the first country in the world to make psychedelics nationally available for medicinal use. Authorised psychiatrists will be allowed to prescribe MDMA as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression (Therapeutic Goods Administration, 2023). For these specific uses, psilocybin and MDMA will be listed as Schedule 8 (Controlled Drugs) medicines in the Poisons Standard. For all other uses, they will remain in Schedule 9 (Prohibited Substances) which largely restricts their supply to clinical trials.

The next article in this series will explore the evidence for MDMA-assisted therapy.

Key takeaways

- The current research evidence indicates psychedelics are only effective for the treatment of mental health conditions when combined with psychotherapy.

- The effects of psychedelics depend on the pharmacology of the substance and contextual factors. The context includes the mindset of the user, the setting in which the drug is taken and the relationship with the therapist.

- Clinical trials for psychedelic-assisted therapy currently employ a set and setting model of therapy that includes preparation for the medicine session, support during the session in which the drug is given and integration following the session.

- PAT requires a psychiatrist to administer the psychedelic and provide medical monitoring, and trained psychotherapists.

- Psychedelic-assisted therapies involving as little as a single dose can promote neuroplastic changes that lead to long-term changes in beliefs and behaviors associated with improvements in mental health.

- The use of psychedelics to treat mental illness outside of clinical trial settings is prohibited in most countries. Australia is the first nation to authorise psychiatrists to prescribe MDMA for PTSD and psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression.

References

- Andersen, K. A. A., Carhart-Harris, R., Nutt, D. J., & Erritzoe, D. (2021). Therapeutic effects of classic serotonergic psychedelics: A systematic review of modern-era clinical studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 143(2), 101-118. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13249

- Argento, E., Christie, D., Mackay, L., Callon, C., & Walsh, Z. (2021). Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy After COVID-19: The Therapeutic Uses of Psilocybin and MDMA for Pandemic-Related Mental Health Problems. Front Psychiatry, 12, 716593. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.716593

- Australian Psychological Society. (2021). Position statement: Psychologists and psychedelic-assisted therapy. https://psychology.org.au/getmedia/1549bc9d-69da-4085-91b6-68e489ba696d/050922aps-ps-psychedelics-p2.pdf

- Browne, G. (2023). The Therapy Part of Psychedelic Therapy Is a Mess. Wired. Retrieved 5 May 2023 from https://www.wired.co.uk/article/psychedelic-therapy-mess

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Friston, K. J. (2019). REBUS and the Anarchic Brain: Toward a Unified Model of the Brain Action of Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 71(3), 316. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.118.017160

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., Roseman, L., Haijen, E., Erritzoe, D., Watts, R., Branchi, I., & Kaelen, M. (2018). Psychedelics and the essential importance of context. J Psychopharmacol, 32(7), 725-731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881118754710

- de Vos, C. M. H., Mason, N. L., & Kuypers, K. P. C. (2021). Psychedelics and Neuroplasticity: A Systematic Review Unraveling the Biological Underpinnings of Psychedelics. Front Psychiatry, 12, 724606. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.724606

- Ducharme, J. (2023). Psychedelics May Be Part of U.S. Medicine Sooner Than You Think. TIME Magazine. Retrieved 10 May 2023 from https://time.com/6253702/psychedelics-psilocybin-mdma-legalization/

- Garcia-Romeu, A., & Richards, W. A. (2018). Current perspectives on psychedelic therapy: Use of serotonergic hallucinogens in clinical interventions. International Review of Psychiatry, 30, 291-316. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1486289

- George, D. R., Hanson, R., Wilkinson, D., & Garcia-Romeu, A. (2022). Ancient Roots of Today’s Emerging Renaissance in Psychedelic Medicine. Cult Med Psychiatry, 46(4), 890-903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-021-09749-y

- Hartogsohn, I. (2017). Constructing drug effects: A history of set and setting. Drug Science, Policy and Law, 3, 2050324516683325. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050324516683325

- Kaelen, M., Barrett, F. S., Roseman, L., Lorenz, R., Family, N., Bolstridge, M., Curran, H. V., Feilding, A., Nutt, D. J., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2015). LSD enhances the emotional response to music. Psychopharmacology, 232(19), 3607-3614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-015-4014-y

- Kelly, D. F., Heinzerling, K., Sharma, A., Gowrinathan, S., Sergi, K., & Mallari, R. J. (2023). Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy and Psychedelic Science: A Review and Perspective on Opportunities in Neurosurgery and Neuro-Oncology. Neurosurgery, 92(4). https://journals.lww.com/neurosurgery/Fulltext/2023/04000/Psychedelic_Assisted_Therapy_and_Psychedelic.5.aspx

- Law, T. (2022). Colorado Voted to Decriminalize Psilocybin and Other Psychedelics. TIME Magazine. Retrieved 9 May 2023 from https://time.com/6232212/colorado-decriminalizes-psychedelics-psilocybin-proposition-122/

- Leary, T. (1964). The psychedelic experience; a manual based on the Tibetan book of the dead. University Books.

- Leary, T. (1966). Programmed Communication During Experiences With DMT. The Psychedelic Review, 1(8), 83–95. https://maps.org/research-archive/psychedelicreview/v1n8/01883lea.pdf

- Leary, T. (1970). The Religious Experience: Its Production and Interpretation. Journal of Psychedelic Drugs, 3(1), 76-86. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.1970.10471364

- Leary, T., Litwin, G. H., & Metzner, R. (1963). Reactions to psilocybin administered in a supportive environment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 137, 561-573. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-196312000-00007

- McClure-Begley, T. D., & Roth, B. L. (2022). The promises and perils of psychedelic pharmacology for psychiatry. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 21(6), 463-473. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-022-00421-7

- McElrath, K., & McEvoy, K. (2002). Negative experiences on Ecstasy: the role of drug, set and setting. J Psychoactive Drugs, 34(2), 199-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2002.10399954

- Metzner, R., & Leary, T. (1967). On programming psychedelic experiences. Psychedelic Review, 9, 5–19. https://maps.org/research-archive/psychedelicreview/n09/n09005met.pdf

- Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. (n.d.). Expanded Access Program for MDMA-Assisted Therapy for Patients with Treatment-Resistant PTSD (EAMP1). Retrieved 9 May 2023 from https://maps.org/mdma/ptsd/expanded-access/

- Nichols, D. E. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacol Rev, 68(2), 264-355. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011478

- Nutt, D. (2019). Psychedelic drugs-a new era in psychiatry? Dialogues Clin Neurosci, 21(2), 139-147. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.2/dnutt

- Passie, T. (2018). The early use of MDMA (‘Ecstasy’) in psychotherapy (1977–1985). Drug Science, Policy and Law, 4, 2050324518767442. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050324518767442

- Reardon, S. (2023). US could soon approve MDMA therapy — opening an era of psychedelic medicine. nature. Retrieved 10 May 2023 from https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-01296-3

- Reiff, C. M., Richman, E. E., Nemeroff, C. B., Carpenter, L. L., Widge, A. S., Rodriguez, C. I., Kalin, N. H., & McDonald, W. M. (2020). Psychedelics and Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry, 177(5), 391-410. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010035

- Rucker, J. J. H., Iliff, J., & Nutt, D. J. (2018). Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs. Past, present & future. Neuropharmacology, 142, 200-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.040

- Sarris, J., Pinzon Rubiano, D., Day, K., Galvão-Coelho, N. L., & Perkins, D. (2022). Psychedelic medicines for mood disorders: current evidence and clinical considerations. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 35(1). https://journals.lww.com/co-psychiatry/Fulltext/2022/01000/Psychedelic_medicines_for_mood_disorders__current.5.aspx

- Shewan, D., Dalgarno, P., & Reith, G. (2000). Perceived risk and risk reduction among ecstasy users: the role of drug, set, and setting. International Journal of Drug Policy, 10(6), 431-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-3959(99)00038-9

- Tai, S. J., Nielson, E. M., Lennard-Jones, M., Johanna Ajantaival, R. L., Winzer, R., Richards, W. A., Reinholdt, F., Richards, B. D., Gasser, P., & Malievskaia, E. (2021). Development and Evaluation of a Therapist Training Program for Psilocybin Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression in Clinical Research. Front Psychiatry, 12, 586682. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.586682

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. (2023). Change to classification of psilocybin and MDMA to enable prescribing by authorised psychiatrists. Retrieved 8 May 2023 from https://www.tga.gov.au/news/media-releases/change-classification-psilocybin-and-mdma-enable-prescribing-authorised-psychiatrists

- Vargas, M. V., Dunlap, L. E., Dong, C., Carter, S. J., Tombari, R. J., Jami, S. A., Cameron, L. P., Patel, S. D., Hennessey, J. J., Saeger, H. N., McCorvy, J. D., Gray, J. A., Tian, L., & Olson, D. E. (2023). Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Science, 379(6633), 700-706. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adf0435

- Wallace, A. F. (1959). Cultural determinants of response to hallucinatory experince. AMA Arch Gen Psychiatry, 1, 58-69. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1959.03590010074009

- Winkelman, M. J. (2021). The evolved psychology of psychedelic set and setting: Inferences regarding the roles of shamanism and entheogenic ecopsychology. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 619890. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.619890