Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based therapy to treat anxiety. This article looks at how a person with probable generalised anxiety disorder might be treated with CBT.

Related articles: Assessing and Treating Anxiety, Reviewing Generalised Anxiety Disorder, Treating Generalised Anxiety with Motivational Interviewing.

Introduction

Our previous article in this series (Reviewing Generalised Anxiety Disorder) outlined the prevalence, symptoms, and factors related to generalised anxiety disorder (GAD); it offered two screening instruments. In this second piece of the series, we examine how GAD might be treated through the lens of cognitive behavioural therapy, or CBT: probably the most extensively evidence-based therapy for many conditions, and certainly for anxiety disorders. We introduce you to Heather, the case example through which we outline the types and progression of therapeutic tasks which you might expect to see for someone feeling chronically anxious. We assume here that you know a bit about GAD (if you do not and did not read our first article in the series, it would be a good idea to go back and do that before reading this one) and a bit about CBT (for unfamiliarity with this approach, we recommend browsing the MHA course catalogue for CBT courses and resources).

Heather: Overwhelmed now, afraid for the future

The therapist reporting this case received a request for therapy from Heather, a 35-year-old who presented with chronic anxiety, which focused on her presenting issue of climate change fears. Heather, a psychologist and university-educated woman who worked in a public counselling agency, fretted constantly about most things, but frequently cycled back to concerns about the future and what would become of her and her whole generation. She lived in a state where many hectares of forest had been burned in recent years in massive wildfires, although her community was well away from where the fires had occurred and was protected somewhat by geographical features. Heather wanted to start a family but said that she was afraid to bring a child into the world that she could see coming. It was revealed at intake that she often felt overwhelmed in her work with counselling clients (both individual and group) and frequently felt the need to stay late to complete the extensive paperwork required for each client (for a related topic, read Notetaking for Therapists: Best Practices and Innovations).

Heather had been raised primarily with highly protective but not affectionate grandparents, as her mother worked full time to support Heather and the grandparents. Heather’s father, not around for most of her life, had barely survived a terrible flooding disaster as a young person in his native country. Heather’s mother, like her parents, loved Heather and cared for her physical welfare, but was not demonstrative; she had to work long hours at her job as a solicitor, so she had little time to spend with Heather. Both Heather’s grandparents and her mother had very high standards for behaviour, which Heather worked hard to meet; she felt aghast at the thought that she would displease or disappoint anyone.

Heather’s partner also worked long hours in a professional capacity, so Heather was in the habit of ringing him several times during the day “just to make sure he was ok”.

The therapist soon learned that Heather worried about most things: whether she was performing ok on her job, whether they would ever be able to afford their own home, whether a client would make a complaint about her (both her individual and group clients liked Heather a lot, as she went to great lengths to build rapport), and whether her friends still liked her, as many had gone on to have children and were not as available to hang out anymore. In the end, though, Heather always came back to the dire state of the rapidly-warming globe.

At intake, Heather disclosed symptoms of a general sense of unease or being on edge, frequent fatigue and irritability, sleep disturbance, muscle tension/aches, occasional nausea, frequent need to urinate, and serious difficulty concentrating. She had had the symptoms for over a year, but as a psychologist, she believed that she should be able to sort her own problems out and had not previously sought help. Heather experienced occasional low mood; when she had an episode ongoing for several weeks, she realised it was time to get professional assistance.

How should someone like Heather be treated?

Formulation of the treatment program

After ruling out possible physical disease/disorder through a physical checkup, any therapist treating GAD must target the three principal “systems” of anxiety: (1) the physiological level (aided by relaxation training); (2) the mental level (for which there is cognitive restructuring), and (3) behavioural (to do with preventing the worry behavior) (Brown et al, 2001; Gaspar, n.d.). Thus the common program components used to treat GAD consist of: psychoeducation, self-monitoring, cognitive therapy, worry exposure, relaxation training (and – for some therapists and clients – the associated discipline of mindfulness), worry behaviour prevention, time management, and problem-solving. We check out what is involved in each, and how they came together in Heather’s case.

Psychoeducation

Heather knew that she was in an uncomfortable place in terms of her mental, physical, and behavioural responses to life situations and events. Moreover, as a mental health professional, she knew about the causal relationship between thoughts, body sensations, feelings, and behaviours. Yet, like other “worry warts”, she did not believe that she could control her anxiety, which is partly why it upset her so much. And, despite familiarity with CBT, she was taken aback to learn that she would need to actually spend specified periods of time each day doing what she was fretting about: getting into the content of her worry.

Thus, some of the elements in the psychoeducation portion of the treatment program included:

- Clarifying both Heather’s and the therapist’s expectations for the work

- Reminding Heather about how the collaborative empiricism of CBT works, and what it can accomplish

- Identifying for Heather the three components of anxiety (physiological/cognitive/behavioural) and applying this understanding to her particular symptoms

- Discussing what constitutes helpful and maladaptive worrying (to some degree, Heather’s symptoms needed to be “normalised”, or seen for the partially adaptive response that they were)

- Explaining the various treatment components – and the rationale behind using them

- Training Heather in the process of completing the self-monitoring forms

- Emphasising the crucial importance of gathering “data” via the completion of the homework assignments (Brown et al, 2001; Gasper, n.d.)

Preliminary steps and self-monitoring

The therapist first asked Heather to get a complete physical examination, which did not turn up anything remarkable. Second, she was asked to complete the GAD-7, which revealed a score of 9, or “moderate” anxiety.

Heather was then asked to do self-monitoring exercises to empirically discover the patterns, situations, conditions, and events that were generating and maintaining her anxiety. The collaborative aspect would come into play as Heather brought the results back to session and interpreted them jointly with the therapist. The self-monitoring exercises would provide valuable information for the formulation and evaluation of the program for the following reasons:

- The therapist would be able to gauge the Heather’s response to treatment by obtaining precise information on clinical variables such as daily levels of anxiety and depression, positive emotions, and amount of time spent worrying.

- The data could provide a clearer picture of her anxiety and worry episodes in terms of the factors that precipitate an episode, the thoughts that generate anxiety, and the methods/behaviours Heather tended to engage to reduce worry or anxiety.

- The request to complete homework sheets could establish whether Heather was complying with between-session work and whether, therefore, the whole treatment program had integrity.

- Heather came to accept that her role in the treatment was just as important as that of the therapist. The data needed to be collected empirically (through on-going self-observation as opposed to recall, which would delete or distort too much data) and no one else could do it.

Weekly Record of Anxiety and Depression

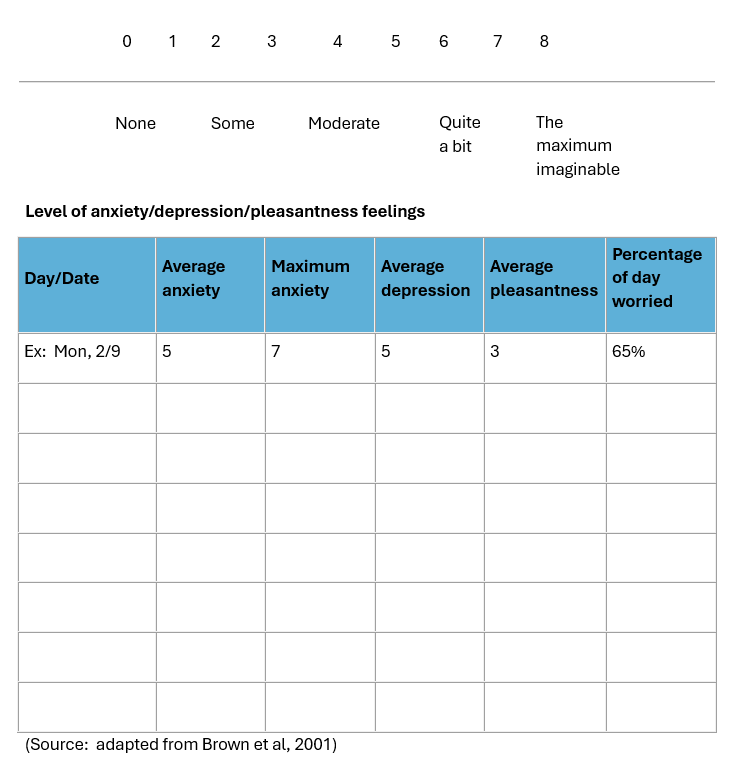

The therapist assigned Heather the task of completing the Weekly Record of Anxiety and Depression (click here to download the image below). It asked her to record, before going to bed, the following ratings, using the included scale.

- Her average level of anxiety (taking all events and factors into consideration)

- Her maximum level of anxiety experienced during the day

- Her average level of depression

- Her average level of positive feeling (also referred to as “pleasantness”)

- The percentage of the day she felt worried, on a 0 to 100 percent scale, where 0 stands for “no worry” and 100 represents being worried all day long while awake.

Overall, Heather reported moderate levels of anxiety, but these shot up to 7 or 8 right before she would facilitate a session of group therapy and occasionally upon reading or hearing news articles about the worsening climate. She felt blessed to not have frequent depression, but did dip on occasion (with the latest episode of low mood catapulting her into therapy). These mild-to-moderate bouts resulted in her overall score of “pleasantness” or positive feeling only achieving an overall score of around 4. She was uncertain what her percentage of worry was during a day, but she reckoned that varied between 35-40% on good days but leaping up to 65-70% on days when worries “attacked” her more.

Cognitive therapy

This component may be regarded as “first among equals” in any treatment program for GAD. During the initial psychoeducation portion of the treatment, the therapist reminded Heather about the nature of anxiogenic cognitions, including explanation of the concept of automatic thoughts, the situation-specific nature of anxious predictions, and reasons why the inaccurate thoughts responsible for anxiety persist – unchallenged – over time. As part of the psychoeducation, the therapist strongly imbued Heather with the basic principle of cognitive therapy: that, in the case of excessive anxiety, it was her interpretations to situations rather than the situations themselves which were causing the negative emotions experienced as a consequence.

Identifying anxiety-making cognitions

Here the therapist worked mostly with examples generated by Heather to help her identify specific interpretations/predictions she was making which were causing trouble.

The first step was to identify such cognitions. Many of the early ones revolved around a bleak sense of hopelessness about the future, given climate change; Heather professed concern about bringing a child into such a world, even though she and her partner both wanted children. The therapist kept listening, though, and it soon became apparent that Heather worried about things from most domains of her life. She feared that her partner would become unwell at work (although he was healthy), or perhaps lose interest in her. She also declared, “I’m not a good psychologist, so my clients might not improve; they might even file a complaint against me”. Thus, finances were always of concern due to feared job loss. And when would they be able to buy a home? Heather also fretted, “I’m probably not that interesting as a friend; people aren’t very available to hang out, and even my partner might get bored with me.”

Early on for both clients and new therapists, the challenge is to discover the anxiogenic cognitions mostly responsible for the negative affect. Therapists can use several techniques for this, including evoking imagery and also role playing, but in Heather’s case, what worked well was to simply get her to be instantly aware of changes in anxiety level, so that she could learn to ask herself, “My anxiety just jumped from 1 to 7; what was I thinking just then that may have caused this?” The therapist also used shifts in her level of affect in session to bring forth automatic thoughts.

With Heather’s strong mental field and consistent ability to identify automatic thoughts, the therapist was soon able to start the challenge training. This consisted mainly of working with two types of cognitive distortions: “probability overestimation” and “catastrophic thinking”.

Challenging probability overestimation

In probability overestimation, the person magnifies the likely occurrence of a negative event (which is actually unlikely to occur) (Otto, n.d.). Heather had remarked multiple times that she (and her generation) would have no future because the climate catastrophe would make most areas uninhabitable for one reason or another. She would add that any child brought into such an environment could not possibly live a happy, healthy life. While negative climate predictions have abounded in many areas of the world, the wider region in which Heather lived had not experienced, apart from the state’s wildfires a few years back, major weather adversities, such as hurricanes, flooding, or severe drought. When challenged about this, Heather remarked that they had just been “lucky” so far. As the therapist worked with her to challenge various thoughts and beliefs in this regard, Heather’s estimation of the probability of a major weather event destroying her home and rendering her community uninhabitable declined steadily, from 80% to around 20%. Meteorologists in the area, meanwhile, estimated the probability of a terrible weather event at closer to 5 or 10%, and added that the community, and the whole state, had put in place many mitigating circumstances should Mother Nature go on a rampage.

Eventually, they were able to jointly generate several more probable alternatives to this worst case scenario, such as that a weather event could occur but that most homes would be spared, or that a weather event might destroy or damage some homes, but they could be rebuilt with insurance monies.

Countering catastrophic thinking

The cognitive distortion of catastrophic thinking is defined as the tendency to view an event as “intolerable”, “impossible to manage”, or something the person would not be able to cope with, when in reality it is less catastrophic than it may appear to be. Not only do people with GAD tend to believe that they will be unable to cope with perceived “catastrophes”, but also, such individuals tend to draw extreme conclusions or ascribe dire consequences to minor or unimportant events.

Regarding potential adverse weather events, the therapist assigned Heather the homework of checking out what resources existed in the community for evacuation to safe places. She was also directed to check on her specific car and contents insurance, to make sure that it was adequate. Eventually reporting back that her community was fairly well prepared for adverse events and that her insurance was of “premium” quality, Heather’s catastrophic thinking drifted to other areas of her life, such as the occasional grim faces that people in her therapy groups would display. In these instances, Heather often had a chain of negative thoughts, starting with, “Sally has a very unhappy look on her face. She must think I’m doing a terrible job facilitating this group. She’s probably going to make a complaint about me. I’m likely to lose my job and no one else will hire me. We won’t have enough money to make ends meet. . . .”

Obviously, countering this chain of catastrophic thoughts was important to Heather’s peace of mind and was a skill on which she worked prodigiously with the therapist, eventually coming to see how her affection-starved childhood had led her to look externally for signs of approval, leading to hypersensitivity around responses and signals from others. She began to learn how to subtly enquire as to whether clients were ok, and usually discovered that her clients were preoccupied with their own problems at such times.

Some clients confuse these two cognitive distortions and may need assistance in differentiating between the two. The therapist can help by emphasising the distinction on the basis of likelihood (probability overestimating) and on the aspect of perceived inability to cope or to ascribe overly dire consequences to minor events (catastrophic thinking). The two in any case are often entwined in the client’s worry chain (Brown et al, 2001).

The fine art of countering

Let’s focus for a moment on countering. Heather’s therapist knew that engaging her in “Pollyanna” thinking (i.e., “All is fine; don’t worry”) would not work. Rather, the process was one of examining the validity of interpretations made and helping Heather replace inaccurate cognitions with realistic, evidence-based ones. He advised Heather that she could do this if she followed these guidelines: (1) that thoughts be considered as hypotheses rather than facts (so they can be supported or refuted by evidence); (2) that all available evidence be used to examine the validity of beliefs held; (3) that all possible alternative predictions or interpretations of an event/situation be explored. Following these guidelines would result, the therapist said, in a much more realistic appraisal of the odds of the negative event occurring. Similarly, de-catastrophising did not entail asking Heather to view negative events as positive or even neutral. Rather, it asked her to evaluate the actual impact of an event on her, which could then show it as time-limited and/or manageable (Brown et al, 2001).

Worry exposure

Heather’s therapist told her that the worry exposure portion of the treatment should be comprised of the following steps:

- Identifying and recording two or three principal spheres of Heather’s worry, ordered hierarchically from the least distressing or anxiety-provoking worry. Thus, Heather listed: (1) worrying about her partner while he was at work; (2) fretting about looks or gestures of her clients in group therapy; (3) catastrophising about the future habitability of her region and the planet in general.

- Doing imagery training by imagining pleasant scenes (Heather did this well from the outset).

- Practicing vividly evoking the first worry sphere on the hierarchy (her partner at work) by concentrating on the anxious thoughts while trying to imagine the worst possible feared outcome for that sphere of worry (that something would happen to him, or that he would leave her).

- Re-evoking these images and holding them clearly in mind for 25-30 minutes (this step is the crucial one of worry exposure).

- After 25-30 minutes, having Heather generate as many alternatives as possible to the worst possible outcome.

- Getting Heather to then record her levels of anxiety and imagery vividness for various points in the exposure (for example, maximum anxiety during the worry exposure; anxiety levels after coming up with alternatives to the worst possible outcome).

- Getting Heather to then repeat these steps for the second worry (concern about clients’ looks or gestures in the group) on the hierarchy. Generally, when an exposure no longer evokes more than mild anxiety after attempts to evoke vivid images of it (say, 2 on an 8-point scale), the client is allowed to go on to the third worry in the hierarchy: in Heather’s case, that of climate disasters so huge that her home or her region would become uninhabitable (Brown et al, 2001).

Relaxation training

Recent decades have seen a proliferation of relaxation techniques. Chiefly, these can focus on:

- Progressive muscle relaxation

- Calming and centring the mind (e.g., use of a mantra or focus object)

- Deep breathing and other yogic techniques

- Disidentification exercises, such as the Psychosynthesis technique of Body/Feelings/Mind

- Visualisation exercises

- Mindfulness practice

Heather found that a combination of deep breathing and mindfulness worked well for her, as long as she kept the exercises short to avoid restlessness.

Worry behaviour prevention

A study comparing GAD subjects with non-GAD-diagnosed participants with “elevated worry” found that, relative to high worriers, those with GAD had more negative beliefs about worry, a greater range of worry topics, and more frequent and severe negative thought intrusions (Hirsch et al, 2013). These GAD tendencies surely lead to greater worry prevention behaviour. A now-classical study with GAD-diagnosed subjects and non-GAD controls found that greater than 50 percent of the “worry behaviours” of the GAD group were linked to the person carrying out a corrective, preventative, or ritualistic behaviour (similarly to OCD patients executing compulsions; click here to read a case study on working with OCD). Unfortunately, such behaviours are negatively reinforcing in behaviourist terms: that is, doing them results in the “reinforcement/reward” of temporarily reduced anxiety (Craske et al, 1989).

Typical worry behaviours include making frequent phone calls to loved ones at work or at home to “check if they’re ok”, checking and rechecking a recipe several times as each ingredient is added to make sure it is being followed properly, and overstocking the pantry deliberately in case unannounced guests drop by. Similarly to OCD, the useful CBT intervention is to systematically prevent responses that are (functionally) related to worry. The therapist needs to help the client understand how such behaviours are maintaining their anxiety; thus, the procedure involves testing out the client’s belief that a given behaviour is actually preventing dire consequences from occurring; it is called prediction testing. With Heather it took these steps:

- The therapist helped Heather to generate a list of her common worry behaviours.

- Heather self-monitored and recorded the frequency with which each behaviour occurred during the week.

- Heather did a competing behaviour instead of the worry behaviour. For example, instead of ringing her partner at work, she would make a phone call to take care of some business, such as setting an appointment, or to ring a friend.

- Before Heather performed the worry prevention behaviour (e.g., the alternate phone call), the therapist recorded the Heather’s predictions concerning the consequences of response prevention.

After some of the worry behaviour prevention exercises were completed, the therapist and Heather compared the outcome of each exercise to Heather’s predictions. She saw that engaging worry behaviours was not correlated with preventing future negative events happening.

Time management

Many GAD-diagnosed individuals are perfectionistic, thus requiring extra time for some tasks and resulting in other (more important) tasks not being completed; perfectionism also breeds burnout. Heather often stayed late at work, struggling to complete the paperwork that went with her job. With unrealistic standards, she would write more than necessary to ensure that the needed information was included, resulting in long hours and high levels of fatigue. Now she began to work at seeing how she could cut down on what she wrote while retaining the important data.

Problem-solving

Finally, life is made more challenging for GAD-diagnosed individuals because they have difficulties solving the inevitable problems of life. First, there is the tendency to think catastrophically about a problem which has presented itself. Many anxiety-disordered people tend to see problems in a vague or undifferentiated way and sometimes feel so overwhelmed that they are unable to generate any solutions at all (perceiving only a disastrous outcome). CBT principles can help by teaching the client to break problems into smaller, more manageable bits (skills transferred from the cognitive therapy) (Brown et al, 2001).

In Heather’s case, the breaking down into smaller chunks began with the presenting problem of climate change. This was reframed as, “What can you personally do to help the environment?” She made a list of things she could do in her personal life – from using more solar power to buying foods which had travelled fewer “food miles” – and gradually, with the therapist’s help, began to expand into more community-oriented activities, thus doing her bit to reduce climate change in a more expansive way.

Conclusion

While not ignoring Heather’s presenting issue of fears around climate change, he gradually elicited the many domains of Heather’s life where excessive worry thoughts or behaviours were impacting her functionality and collaborated with her to address these, from catastrophic thinking to the perfectionism that brought her close to burnout at work through all the excess hours put in to ensure her impossible standards. Through diligent attention to all the strands of treatment, Heather’s worry levels gradually decreased, replaced by more moderate thoughts and behaviours.

Key takeaways

- The CBT-based therapy program for generally anxious Heather, presenting with climate change fears, needed to target the three principal “systems” of anxiety: (1) the physiological, (2) the mental, and (3) the behavioural.

- The treatment program included psychotherapy, self-monitoring, cognitive therapy, worry exposure, relaxation training, worry behaviour prevention, time management, and problem-solving.

- The cognitive therapy saw Heather identifying anxiogenic cognitions, being challenged on overestimates of probability, and countering catastrophic thinking.

- Heather’s worry behaviour prevention included making a phone call to someone, such as a friend or business she needed to contact, instead of disrupting her partner at work to ask if he was ok.

- Heather collaborated with the therapist to produce a list of ways whereby she could personally work to reduce the impact of climate change.

Anxiety courses and training

Numerous Mental Health Academy courses cover the topic of working clinically with anxiety and anxiety disorders. Click the following links to learn more about each course:

- Anxiety: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment

- Using CBT with Generalised Anxiety Disorder

- Using CBT with Panic Disorder

- Using CBT with Social Anxiety Disorder

- Treating Anxiety with Motivational Interviewing

- Helping Clients with Hoarding Disorder

- Working with Paediatric Anxiety

- Men’s Anxiety, Why It Matters, and What is Needed to Limit its Risk for Male Suicide

- Clinical Applications of Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) for Anxiety

- The Psychopharmacology of Anxiety

Note: MHA members can access 500+ CPD/OPD courses, including those listed above, for less than $1/day. If you are not currently a member, click here to learn more and join.

References

- Brown, T.A., O’Leary, T.A., & Barlow, D.H. (2001). Chapter 4: Generalised Anxiety Disorder. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders, third edition: A step-by-step treatment manual, D. Barlow, Ed. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Gasper, P. (n.d.) Assessment & formulation in CBT. The Marian Centre. Retrieved on 30 June, 2014, from this link.

- Hirsch CR, Mathews A, Lequertier B, Perman G, Hayes S. Characteristics of worry in generalized anxiety disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2013 Dec;44(4):388-95. Doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.03.004. Epub 2013 Apr 12. PMID: 23651607; PMCID: PMC3743042.

- Otto, M.W. (n.d.). Cognitive behavioral treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Boston University: Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders. Retrieved on 6 July, 2014, from this link.