Metacognitive Therapy is a science-backed psychotherapy approach which attributes mental unwellness to unhelpful thinking patterns, aiming to reduce these and change the metacognitive beliefs activating them.

Related articles: What is Interpersonal Therapy?, What is Solution Focused Therapy?, What is Person Centred Therapy?, What is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy?

Jump to section:

Introduction

Beth had made reasonable progress over the several years of doing Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) with her therapist, but when the therapist moved out of state, Beth was forced to find another therapist. In the first session, the new therapist invited Beth to describe what had brought her there. Beth said that, as the child of alcoholics, she had had very little parental attention over the years and consequently had recurring negative thoughts about herself, often feeling that she wasn’t “good enough”. Based on her previous experience, Beth expected the therapist to say, “What evidence do you have for that?” Instead, she nearly fell off her chair when the therapist replied, “Please tell me, what is the point of evaluating how ‘good’ you are?” With that intervention, a whole new – and very successful – chapter in Beth’s healing of childhood experiences began. She later came to find out that it was called metacognitive therapy.

Metacognitive Therapy, an effective, evidence-based psychological treatment for numerous mental disorders, began to be developed in the mid-1980s during the doctoral studies of its originator, Adrian Wells. As the name suggests, it helps clients to think about thinking, revealing unhelpful thinking patterns like excessive rumination and worry, as opposed to focusing on unhelpful contents of thinking: that is, the actual thoughts; in this it is innovative.

In this article, we look at what Metacognitive Therapy is and the mental disorders for which it has a successful “track record”. We explain why it works and briefly outline five steps therapists can take if they wish to work in a metacognitive therapeutic way.

The origins and components of Metacognitive Therapy

Metacognitive Therapy (MCT) is a science-backed psychotherapy approach attributing mental illness to unhelpful thinking patterns like excessive rumination and worry. It aims to reduce such thinking styles and change the metacognitive beliefs that activate them (Shang, 2021).

Briefly, the history of Metacognitive Therapy

Wells, the developer of MCT, had an interest in information processing theory and the role of self-attentional processes in anxiety. As part of his graduate studies, Wells had begun testing mechanisms and underlying concepts that would later form the metacognitive model. He was influenced by colleagues who demonstrated effects of heightened self-focused attention across numerous psychological disorders. In those days when therapies such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Rational-emotive Behavioural Therapy (REBT) were gaining popularity, Wells was already contrasting those therapies’ centring on the content of cognitions with the concern he felt should be placed instead on attentional processes and thinking styles, such as worry (Wells & Matthews, 1994). Around this time, some theorists were proposing theories of self-awareness with a dichotomy in the direction of attention: whether it was directed inward toward the self or outward toward the environment. Further differentiation was made between private and public self-consciousness, and both were shown to correlate positively with social anxiety (Capobianco and Nordahl, 2023).

The Self-Regulatory Executive Function (S-REF) Model is born

Also referred to as the metacognitive model of psychological disorders, Wells and colleague Gerald Matthews (Wells and Matthews, 1994 and 1996) developed the Self-Regulatory Executive Function, or S-REF, Model, which integrated information processing research with Beck’s schema theory. The model argues that any model of disorder should distinguish between levels of control of attention and map the effects of those levels of processing on psychological disorder. Existing theories, they said, did not specify in detail the different levels/aspects of cognition, and that contributed to emotional problems. Thus, this type of analysis would be central to their model, leading to specific predictions about what should be done in treatment and which components of cognition should be targeted (Capobianco and Nordahl, 2023; Wells and Matthews, 1996).

The Cognitive Attentional Syndrome (CAS)

The starting point for the development of the S-REF was the identification and labelling of the cognitive attentional syndrome, or CAS, a cluster of processes activated under stress/threat and presumed to lead to psychological disorder. The CAS consists of repetitive negative thinking in the form of worry, rumination, threat monitoring, and/or maladaptive coping behaviours such as thought suppression; these reduce opportunities for effective self-regulation. Clients with high self-focus (that is: private self-consciousness) would, they maintained, be likely to develop this syndrome (Capobianco and Nordahl, 2023).

Metacognitive beliefs can be positive or negative

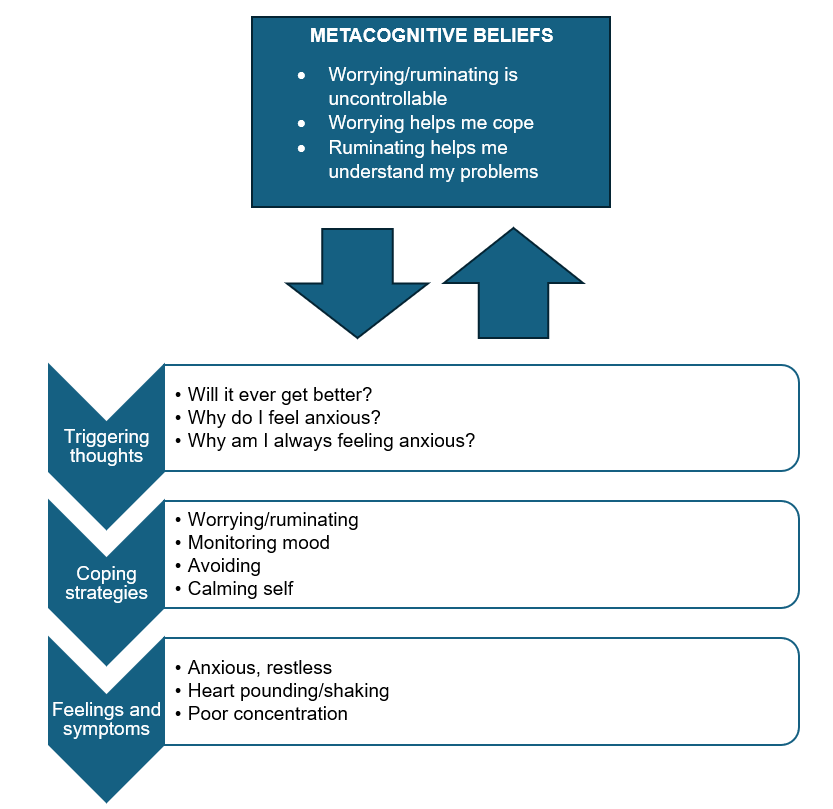

So, how does the CAS fit into the big picture of metacognitive therapy? MCT holds that metacognitive beliefs – that is, beliefs about the way we think – along with the above-noted maladaptive coping strategies such as rumination and worry, generate most psychological disorders. Most people with mental disorders have both positive (but still unhelpful) metacognitive beliefs and negative ones. In the case of anxiety, the person may hold a positive metacognitive belief such as “Worrying helps me cope better” and also some negative beliefs, such as “Worry is uncontrollable”. These cause the person to start worrying about their negative thoughts, which in turn makes them feel even more anxious. But because they don’t believe that the worry can be stopped, they begin to use different (maladaptive) coping strategies – the CAS – to control it (Shang, 2021). The figure (below) shows the progression.

Figure: Metacognitive beliefs to the psychological distress of anxiety

(Adapted from metacognitivetherapy.com, 2021)

What does the research say about Metacognitive Therapy’s effectiveness?

Metacognitive Therapy was developed systematically, driven by its theory rather than like many psychotherapies which are based on clinical observation. Evaluations led from a series of pilot studies, through uncontrolled trials, to RCTs (randomised controlled trials, the gold standard in scientific research – more about it here). Evaluations for Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD), for example, began with a case study in 1995, followed by an uncontrolled trial (2006), and then randomised trials run against active treatments such as applied relaxation and forms of CBT (2010, 2012, and 2018). Feasibility studies of MCT for children and adolescents were published in 2015 and in a group format in 2019 (Capobianco and Nordahl, 2023).

In the last quarter-century, MCT has been trialled in a range of psychological disorders, such as Obsessive-compulsive Disorder (OCD), Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), with recent trials evaluating MCT against CBT (considered the “gold standard” treatment for numerous disorders). This burgeoning evidence base supports MCT as an effective treatment, and it even beats some other psychotherapies (Capobianco and Nordahl, 2023).

Metacognitive Therapy’s efficacy: A systematic review

Specifically, let’s review a few standout investigations, starting with a study by a Danish and a German academic, Nicoline Normann and Nexhmedin Morina, who published a systematic review and meta-analysis (2018) examining the efficacy of Metacognitive Therapy. They reviewed 25 studies which met inclusion criteria; 15 of these were RCTs; only one was studying children and adolescents. The psychological issues that were treated through MCT were depression, bipolar II disorder, GAD, PTSD, cancer distress, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, hyposexual desire disorder, OCD, and grief. 468 patients were analysed in total. Some received MCT and were compared to the rest of the patients that were on a waiting list and not receiving MCT.

In the adult trials, large uncontrolled effect size estimates from pre- to post-treatment and follow-up suggested that MCT is effective at reducing symptoms of the targeted complaints of anxiety, depression, and dysfunctional metacognitions. The strongest results were for anxiety and depression, but the researchers’ findings suggest that MCT may be superior to other psychotherapies, such as CBT, for other disorders as well (Normann & Morina, 2018).

There have been numerous single-issue studies.

Metacognitive Therapy compared to CBT for anxiety

Norwegian researchers compared MCT with CBT in 81 patients with GAD in an investigation using three conditions: treatment with MCT, treatment with CBT, or being on a waitlist (no treatment). The therapists offering the two treatments crossed over halfway through the study to make sure that they did not influence results. The before-treatment, after-treatment, and two-year follow-up results showed that both CBT and MCT effectively treated anxiety, but MCT was more effective (65% v. 38%). A similar study looking at anxiety disorders published in 2021 showed that, even at the 9-year follow-up, those treated with MCT retained their treatment gains over CBT (Nordahl et al, 2018; Solem et al, 2021).

Metacognitive Therapy compared to CBT for OCD in group therapy

In this study, 125 OCD patients received group MCT, with 95 receiving group CBT, each for 12 weeks of treatment. The main finding here is that the group of non-responders to treatment was significantly smaller for the MCT patients than the CBT ones: 9.4% versus 28% for the CBT group, a 22.3% greater response rate for the Metacognitive Therapy treatment. While we can focus on the fact that both groups showed a majority who did reduce OCD symptoms through their treatment, the MCT participants improved much more; thus it is an effective treatment for OCD and can help non-responders to therapies such as CBT (Papageorgiou et al, 2018).

Metacognitive Therapy compared to CBT for depression

In a 2020 study of 172 adults with MDD, participants received either MCT (n = 83) or CBT (n = 89). Receiving up to 24 sessions of therapy by trained clinical psychologists, the participants did not know which treatment they were receiving. Results showed that 74% of those receiving MCT recovered from depression, while 52% of those receiving CBT did; these results were retained at six-month follow-up: 74% v. 56%. The MCT patients not only recovered from depression; they also improved their metacognitive beliefs (that is: beliefs about their ability to control worry, rumination, and attention went from “no control” to “strong control”). They achieved these results with, on average, one fewer therapy session than the CBT participants and recovered from the depression twice as fast as the CBT participants (Callesen, Reeves et al, 2020).

Why does putting attention on metacognition (thinking about thinking) work?

Changes at a meta-level

Metacognitive practitioners are fond of saying that the mind is capable of healing itself. In individuals who do not experience the psychological distress of a condition such as anxiety or depression, a mood or psychological “state” may be experienced temporarily, but then the person is able to self-regulate and thus “shake off” the negative affect. When clients get “stuck” in anxiety, depression, or even more serious psychological distress such as certain forms of psychosis, the metacognitive therapy assumption is that it’s because the client has engaged in biased metacognitive beliefs (as above) which do not allow the mind to self-regulate, in part because the client interprets thoughts and feelings as dangerous and unstoppable. What follows is that “states” become “traits” (i.e., a more enduring feature of the personality). Thus, Metacognitive Therapy works in part because it effectively changes metacognitive beliefs, using such strategies as the following:

- Detached mindfulness: Observing thoughts and feelings in a disidentified way, without engaging or suppressing them, so letting experiences go without trying to control or change them.

- Worry postponement: Reducing the daily time spent worrying by “encasing” worry within a (limited) fixed time window each day.

- Knowledge based strategies: Challenging metacognitive beliefs, such as in attention training and refocusing techniques (Moritz et al, 2019; Shang, 2021: Capobianco & Nordahl, 2023).

Transdiagnostic

Any perusal of the literature on Metacognitive Therapy reveals a foundational feature commonly described as the reason for its burgeoning evidence of effectiveness: it is transdiagnostic in nature. As a 2019 article highlighting new developments for psychosis treatments commented,

“ . . . the CAS in psychosis is similar to that in other mental disorders. Paranoid thinking is likened to the process of worrying: a series of ‘what if’ questions (‘what if the FBI is behind me?’). These questions are perhaps more bizarre than for example in anxiety disorder (‘what if I had cancer?’) but are essentially similar. The response to hallucinatory experiences is comparable to the process of rumination in depression: these patients ruminate about why they feel depressed, patients with psychosis ruminate about why they are hearing these voices and who is orchestrating the phenomena” (Moritz et al, 2019).

Moritz and associates’ examples highlight how MCT is able to be utilised for a range of psychological diagnoses. Formulating the CAS (cognitive attentional syndrome) can assist the client with understanding how dysfunctional cognitive strategies (i.e., both positive and negative metacognitive beliefs) are maintaining paranoid or other unrealistic thinking and hallucinatory experiences. With Metacognitive Therapy, the goal is to increase cognitive flexibility , modify metacognitive beliefs, and decrease the CAS.

Click here for a related article on working with paranoia in counselling.

Techniques based on theory and evaluated before integration

Moreover, Metacognitive Therapy was developed as techniques based on psychological theory of mechanisms, many of them individually evaluated experimentally before being integrated into the MCT “package”. In this category are techniques such as the attention training technique, situational attentional refocusing (developed to counter threat monitoring), metacognitively delivered exposure, and detached mindfulness. This has allowed for systematic evaluation of processes and outcomes and continued appraisal of the fit of techniques with predictions of the psychological theory on which the treatments were developed. The result of this approach has been a more comprehensive and theoretically coherent connection between theory of mechanisms underlying psychological disorders and the psychotherapeutic change techniques used in treatment.

How to “do” Metacognitive Therapy

In some ways, all therapists necessarily engage their clients at a metacognitive level, such as when they invite the client to reflect on how they are thinking about something (the process), as opposed to what they are thinking about (the contents of the thought). Metacognitive Therapy, specifically, is a manualised treatment, and while the therapist aims to tailor the treatment to the client’s specific needs, there is a guide to be followed over the sessions.

In general, Metacognitive Therapy has five steps:

- Step 1: Explain how the client’s specific strategies like worry and rumination maintain their mental disorder/distress.

- Step 2: Help the client to realise that their coping strategies are not effective in solving problems.

- Step 3: Identify the client’s metacognitive beliefs and challenge them through experiments (such as believing they cannot control their worry; if that is what they believe, there is no motivation to try!).

- Step 4: Help the client learn to postpone worry and rumination (accomplished both in session and as homework). The goal is to realise that these are harmless and have no advantages.

- Step 5: Assist the client in learning attention training technique and detached mindfulness to gain flexible attention. This helps focus attention away from negative thoughts and toward meaningful activities, which then allows the mind to self-regulate and thus heal from mental distresses. Detached mindfulness helps the client to become aware of negative thoughts and disidentify from them by stepping back and discontinuing worry and rumination. Near the end of the therapy, the therapist focuses on helping the client to reverse any residual maladaptive coping strategies, such as avoidance or reassurance seeking, preventing relapse (Shang, 2021).

Conclusion

Metacognitive Therapy is not for either therapists or clients who may be “asleep at the wheel”. It takes persistent effort to maintain the focus on a meta-level (that is, to think about thinking rather than descend into thoughts themselves). But every therapeutic insight, such as Wells’ original one that the processes of thinking rather than the contents of thought were the problem, brings us one step closer to being able to help clients with an ever-widening array of presentations in session. Backed up by the burgeoning evidence base and coherent theoretical foundations, Metacognitive Therapy is potentially a powerful ally in this quest.

Key takeaways

- Metacognitive Therapy (MCT) is an evidence-backed therapy focusing not on the contents of a client’s thought, but on their unhelpful thinking patterns or styles: their metacognitions.

- Burgeoning evidence is showing MCT to be as effective as or even more effective than other therapies (such as CBT) for presentations of anxiety, depression, OCD, PTSD, and even some forms of psychosis.

- MCT has a coherent theoretical foundation and is transdiagnostic in nature.

- MCT is manualised; its course of treatment ranges over five general steps, with tailoring for individual client needs.

References

- Capobianco and Nordahl, L. (2023). A brief history of metacognitive therapy: From cognitive science to clinical practice. ScienceDirect. Retrieved on 25 June 2024, from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1077722921001371

- Callesen, P., Reeves, D., Heal, C. et al. (2020). Metacognitive Therapy versus Cognitive Behaviour Therapy in Adults with Major Depression: A Parallel Single-Blind Randomised Trial. Sci Rep 10, 7878 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64577-1

- Metacognitive Therapy Institute. (2018). Metacognitive therapy. MCT Institute. Retrieved on 25 June, 2024 from: https://mct-institute.co.uk/therapy/

- Moritz S, Klein JP, Lysaker PH, Mehl S. Metacognitive and cognitive-behavioral interventions for psychosis: new developments . Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2019 Sep;21(3):309-317. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.3/smoritz. PMID: 31749655; PMCID: PMC6829173.

- Nordahl, H., Borkovec, T., Hagen, R., Kennair, L., Hjemdal, O., Solem, S., . . . Wells, A. (2018). Metacognitive therapy versus cognitive–behavioural therapy in adults with generalised anxiety disorder. BJPsych Open, 4(5), 393-400. doi:10.1192/bjo.2018.54

- Normann, N., & Morina, N. (2018). The Efficacy of Metacognitive Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Front. Psychol., 14 November 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02211

- Papageorgiou C, Carlile K, Thorgaard S, Waring H, Haslam J, Horne L, Wells A. (2018). Group Cognitive-Behavior Therapy or Group Metacognitive Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? Benchmarking and Comparative Effectiveness in a Routine Clinical Service. Front Psychol. 2018 Dec 10;9:2551. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02551. PMID: 30618972; PMCID: PMC6295517.

- Shang. (2021). Does metacognitive therapy work and how? Metacognitive Therapy Central. Retrieved on 25 June, 2024 from: https://metacognitivetherapycentral.com/does-metacognitive-therapy-work-and-how/

- Solem, S., Wells, A., Kennair, L. E. O., Hagen, R., Nordahl, H., & Hjemdal, O. (2021). Metacognitive therapy versus cognitive–behavioral therapy in adults with generalized anxiety disorder: A 9-year follow-up study. Brain and Behavior, 11, e2358. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2358

- Wells, A., & Matthews, G. (1994). Attention and emotion: A clinical perspective. Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

- Wells, A., & Matthews, G. (1996). Modelling cognition in emotional disorder: The S-REF model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34 (11–12) (1996), pp. 881-888.