Solution focused therapy is solution- and future-oriented, assuming that clients have resources to solve their own problems. It collaboratively sets up goals and elicits solutions from the client.

Related articles: What is Person Centred Therapy?, What is Dialectical Behaviour Therapy?, Rethinking Narrative Therapy, What is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy?

Jump to section:

Introduction

There are some situations in life where it is essential to understand how a problem developed. Sometimes, though, such understanding takes a back seat to just needing a timely solution to a problem – as soon as possible, thank you – so that we can get on with things. Proponents of solution focused therapy (SFT) argue that this – the precedence of a timely solution over comprehensive problem examination – is the idea behind this very practical modality; we often need to find solutions more than we need to deeply analyse our problems. Known by various names – including solution-oriented therapy, problem-focused brief therapy, solution focused brief therapy, and even brief therapy – SFT is typically short-duration treatment, although progress is measured by results, not by number of sessions (Seligman, 2006).

This article examines the philosophical base and trends which set the scene for SFT, its chief assumptions and core concepts, and the stages of the treatment.

The many realities and solutions of solution focused therapy

The minute we identify a therapy as being “solution focused”, the logical question is: whose solution are we focusing on? The therapist’s? The client’s? Or some answer to the presenting problem pre-determined by an uninvolved third party? In fact, SFT developed from a branch of postmodern philosophy known as social constructivism, which proposes that, as meaning-making creatures, human beings attach meaning to their own experiences through their interactions with others. Constructivism says that the truth is not “out there” waiting to be discovered, but socially constructed through our everyday interactions and conversations with other people (Freedman & Combs, 1996). If we take as a premise that we are all actively participating in our lives by constructing the realities of them, then two logical conclusions follow: first, no one person (including a very learned, experienced therapist) has a special claim on the truth, and second, there should be a plethora of solutions available, because we have myriad ways of understanding our lives and thereby generating solutions (Archer & McCarthy, 2007). With these understandings, several trends facilitated the emergence of SFT.

The trends that set the scene for solution focused therapy

If we cast our collective minds back to the Freudian couch, we are reminded that treatments in the early days of psychotherapy were anything but brief, and certainly not solution focused. What trends, we can ask, have dovetailed to create a receptive climate in which a practical, goal-oriented, short-term approach such as SFT could flourish? For start, the managed health care movement in the United States and many other Western countries steers treatments in the direction of briefer therapies (e.g., Behavioural Activation Therapy) on the assumption that they will be less expensive and (hopefully) more efficient for the clients/patients. A related factor is that current health delivery systems rely on tangible goals and outcomes. While the tenets of SFT do not lend themselves to empirical research, the approach is nevertheless highly practical.

A third factor could be loosely termed a humanitarian concern with desiring to help people – often those with limited resources – do something to create change they desire. Rising rates of anxiety, depression, and other mental health conditions speak to the pressing need to work out how to help as many people as possible with typically constrained resources. Shorter-term, solution-oriented approaches which do not spend time delving into past histories match well the emphasis on creating the maximum amount of change in a minimal amount of time. Finally, solution focused practitioners believe that, once things begin to improve for clients, the clients – through employing skills that they have learned in session – will be able to keep the ball of change rolling for themselves (Archer & McCarthy, 2007).

Assumptions of solution focused therapy

While solution focused therapy is not based on extensive theories of human personality development, it does have a few primary ideas that govern the types of interventions used. First, while its therapists assume that clients’ complaints stem from their world view, solution focused therapists also are quick to observe that every human being is unique, possessing a different genetic makeup, history of development, and set of patterns attached to meaning than any other human being. Therefore, the potential solutions to client problems will also be unique for each individual, and although therapists can draw on their (the therapist’s) experience, they must also be open to creative solution possibilities for each client. The encouraging news is that solution focused therapists base their suggestions for change on clients’ conception of their lives without their symptoms, figuring that any change will have a ripple effect, generating behaviour change to the whole system (Seligman, 2006; Archer & McCarthy, 2007). Here’s how it may work.

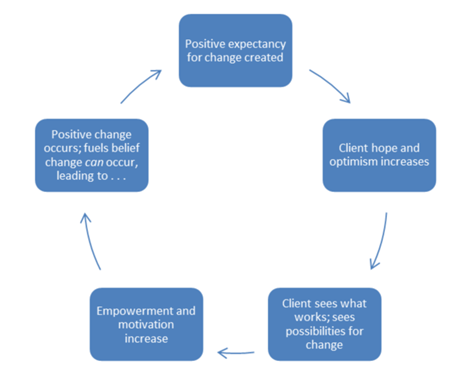

The cycle of change, solution focused style

The assumption is that people have the ability to resolve their difficulties successfully, but they may have temporarily lost confidence, direction, or awareness of resources. Therapists assume that clients are doing the best they can at any given moment. Rather than giving advice (which is, subtly, a message that the client cannot handle the issue themselves), solution focused therapists focus on increasing clients’ hope and optimism by creating expectancy for change, even small change. People thus become more aware of what is working and what is not. Becoming aware of possibilities for positive change, their empowerment and motivation increase; the positive change fuels their belief that change can happen, which enhances motivation and efforts to change, leading to even more positive changes (Seligman, 2006). The figure (below) demonstrates the cyclical nature of effecting positive change.

Figure: Solution focused assumption for how change works

Trust the client’s truth and focus on their preferred futures

Solution focused therapy helps clients to achieve their preferred outcomes through evoking and co-constructing solutions to their problems, emphasising their resources, strengths, and personal qualities. Hence, its therapists further assume:

- Clients have ideas about their preferred futures

- Clients are already implementing constructive, helpful actions (or else things would be worse)

- Clients have myriad competencies and resources, many unacknowledged by themselves and others

- It is more helpful to focus on the present and the future, using the past mainly as a source of evidence for prior successes and skills

- It can be useful to find explanations for problems, but it is not essential, and in some cases can delay constructive change

- Constructing solutions is a separate process from problem exploration

- The “truth” of a client’s life is negotiable within a social context; fixed objective “truths” are unattainable. Clients’ lives have many truths (O’Connell, 2006).

The nature of reality and problems

As we’ve noted, “truth” in solution focused approaches is a personal, individually-negotiated phenomenon (a similar perspective to Narrative Therapy). So is reality, given that solution focused therapists do not believe that there is one right way to view things. O’Hanlon & Weiner-Davis (1989) write that, by helping people “negotiate a solvable problem” (p 56) or possibly “dissolve the idea that there is a problem” (p 58), therapists can help people to set meaningful, viable goals and achieve efficient resolution of their presenting issues. The other important thing to remember is that, because reality is not fixed and change cannot not happen, there are exceptions to the problem the client brings, and times when the problem is not as much in effect. These times give clues to effective solutions. Clients gain further impetus to change as they identify the exceptions and the conditions that created them (Seligman, 2006).

Core concepts of solution focused therapy

You may be able to predict some of the core concepts from an understanding of the basic assumptions made in solution focused therapy. Suffice it to say that many of them have to do with getting a perspective that will be helpful toward finding a solution, even if they are not related to the solution. Let’s examine them.

Solutions are not necessarily related to problems

Recall that solution focused therapy emanates from the social constructivist postmodern philosophy. Thus, it is not necessary to know what a problem is in order to solve it; solutions are often, say the theorists, unrelated to the problems they were intended to solve. SFT developed in the first place when de Shazer and colleagues asked families with whom they worked to identify what they did not wish to change. This intervention had the effect of changing how both counsellors and families understood their lives and the options they had for change. What de Shazer observed was that, often, the families’ proposed solutions were unrelated to the problems as the families had presented those to the counsellors. They concluded that understanding the problem in a deep and detailed way could even be counterproductive because, again, the focus was back on the problem (Archer & McCarthy, 2007).

Maintain a future orientation

Imagine this scenario. You are a solution focused therapist, and your client has been speaking for some minutes now about how horrific her past was leading up to her traumatic event. As a solution focused person, you have a future orientation. What do you do: interrupt her? Tell her that that is all fine, but not relevant and therefore not interesting to you? Solution focused therapists don’t spend a lot of time asking many questions about the history of a particular problem, but when clients volunteer it, they use the information to find out what clients have learned as a result of the experience, what issues they need to leave behind now, what they wish had happened differently, and what difference it would make now in their lives if that had actually happened (O’Connell, 1998). A future orientation is a good reminder that the past cannot be changed, but it does get in the way of change in that clients don’t move on while they are looking for insight into the causes of their problems (Lipchik, 2002).

Focus on strengths

Only the client, not the therapist, has the power to create change (de Shazer, 1988). The good news here is that the client – the therapist believes – has the ability to find solutions to identified problems in creative, resourceful ways. “Look,” the therapist may point out, “You made it this far in life, and you had the strength to get here to ask for help.” This is evidence that the client is the expert on his/her own life and may have very useful ideas for how to sort things out. This quiet assumption can be crucial in helping clients to inventory their available skills and frame life situations in such a way as to be able to deploy their resources toward effective solutions (Archer & McCarthy, 2007).

Change is inevitable

There is always change occurring in the outer world – at global, national, community, and family levels – but even if there weren’t, we human beings would have to adapt to change because it is occurring within us as well. It is inevitable that much of it will be beyond our control, and that some of it will impact us negatively. The key to living a satisfied life lies in an incessant quest for creative ways to resolve the difficulties that come our way, and to accept that even small changes can yield large benefits (Archer & McCarthy, 2007).

The white in the black

As dire as the situation the client describes is, solution focused therapists never accept events as totally negative (or totally positive). Although it is clients’ tendency to describe their experiences in a black-and-white way – and then to continue seeing them as “black”, thus precluding solution-finding – solution focused therapists understand that even the most serious situations offer opportunities for creative problem-solving, growth, and change. Thus, they continue to look for exceptions to problems and signs of client strengths in negative experiences. They want to know: what has kept the client going in such awful circumstances? How can that be built on for future change? (Archer & McCarthy, 2007).

What resistance? There is no such thing

Let’s say for a moment you are working with Lianne, who doesn’t appear to be taking your suggestions on board. You head to your supervisor and lament, “I don’t know what to do. She’s just putting up so much resistance.” If your supervisor is working from a solution focus, you might be surprised to hear back: “Resistance? What do you mean? There is no such thing.” The concept of resistance originally was used in Freud’s day to describe patients who tried to protect their egos by “resisting” interpretations made by their analysts: that is, by not being compliant with the therapist’s suggestions for change. This perspective totally does not work for solution focused therapists! Rather, if you are a solution focused therapist and your client is not taking on your suggestions, the onus is on you to understand your client’s goals, or how to reach them, better. If/when you have the frustration of slow progress with your client, it may be time to make the intervention: “What do you think should be done at this time to make your situation better?” (Lipchik, 2002). Here are some tips to support a clients’ journey towards acceptance (in cases where they may be resisting change that is likely to lead to positive outcomes).

Simplicity is key

“Complex problems do not always need complex solutions,” said de Shazer (Hawkes, Marsh, & Wilgosh, 1998). Many models of counselling rely on voluminous case notes, a battery of assessment measures, and intricate diagnostic systems to work out what is “wrong” with the client. While all that may occasionally be useful, solution focused approaches understand how presumptuous it is to assume that one knows how difficult the problem appears to be from the client’s perspective. More appropriately, the solution focused therapist would ask: “How would the client like the situation to change?” “What are his or her ideas about potential solutions?” In solution focused mode, even simple ideas like taking a walk or a hot bath or going on holiday may be worthwhile solutions if they offer the opportunity for change or improvement (Archer & McCarthy, 2007).

Given this set of understandings about solution focused therapy, what sort of phases does the treatment go through en route to a successful termination? We look briefly at that now.

Stages in solution focused therapy treatment

Brief therapies are likely to have a more well-defined structure, and solution focused therapy is no exception, proceeding typically through these seven stages (de Shazer, 1985):

Stage 1: Identifying a solvable complaint

The operative word here is “solvable”. By undertaking that whatever the client brings can be transmuted into something which is within the client’s power to solve, the therapist not only facilitates development of goals and interventions, but also immediately helps to promote change. For example, the presenting desire to “make my husband stop abusing me” is not readily within the client’s hands to change, but “staying strong and taking care of myself while my husband is abusive” is within the client’s control. Therapist questions should communicate optimism and expectancy for change in order to empower and encourage. Difficulties are normal, so a typical question might be, “What led you to make an appointment now?” rather than “What problems are bothering you?” or “What do you wish to change?” rather than “How can I help you?”

Solution focused therapists do not pathologise presenting issues/complaints; rather, those are seen as evidence that something has gone awry in the client’s interactions with others (related reading: Is Your Client Mentally Ill or Just Having a Tough Time?). People often keep doing the same thing over and over again in their interpersonal relationships, even though the strategy is unsuccessful. As a result, “the solution becomes the problem” (Weakland et al, 1974, p 151). Solution focused therapy believes that by helping to correct the problematic interactions, many complaints can be alleviated.

Stage 2: Establishing goals

Clients collaborate with their therapists to determine goals that are specific, observable, measurable, and concrete. Goals usually are one of three types: (1) those that change the doing of the problematic situation; (2) those that change the viewing of the situation or frame of reference; and/or (3) those that help clients access resources, solutions, and strengths (O’Hanlon & Weiner-Davis, 1989). Questions presume success, asking, for example: “What will be the first sign of change?”, “How will you know when this treatment has been helpful to you?”, “How will I be able to tell?” It is at this stage that the famous solution focused technique, the miracle question, is often heard; it asks clients to imagine that a miracle has occurred, and the problem is solved; how will the client (and possibly others) know?

Stage 3: Designing an intervention

Therapists at this stage draw on both their creative understanding of treatment strategies in conjunction with their knowledge of their clients to encourage change, even very small change. They would typically ask the client questions such as: “What worked in the past for similar situations you dealt with?” “What changes have already occurred?” “How did you make that happen?” “What would you need to do to get that to happen again?”

Stage 4: Generating strategic tasks to promote change

Like any worthy executive, the therapist should write down the strategic tasks generated with the client, to ensure that the client both understands and agrees to them. The tasks are carefully planned to maximise client cooperation and success, and people are praised for their efforts and for the strengths they draw on in completing their tasks. De Shazer’s delightful metaphors for different client types help ensure that each is given an appropriate task:

Visitors or window shoppers are those clients who do not present clear complaints or expectations of change. To these, therapists should give only compliments. To request or suggest tasks to these clients may be to set them up for failure, jeopardising the treatment process.

Complainants are clients who have concerns and do expect change. The problem is that they expect others to do the changing! Therapists here should suggest observation tasks, which can help people become more aware of themselves and their circumstances, and more able to describe what they want. So, for instance, the counsellor might say, “Between now and our next appointment, notice things happening in your life that you want to continue.” Clients don’t have to work too hard or be supremely motivated to do observational tasks, which people tend to do almost automatically once suggested, so there is a high rate of success.

Customers are the clients who genuinely want to take steps to find solutions to their concerns. Action tasks can be suggested with the expectation that they will be completed. The tasks should both empower clients and create changes in their complaints.

Stage 5: Identifying and emphasising new behaviours and changes

At this stage, the therapist becomes the client’s cheering squad, providing compliments and highlighting areas of strength, competence, and success with questions such as: “How did you make that happen?”, “Who noticed the changes?”, and “How did things go differently when you did that?” Notice that, in this languaging, the problem is viewed as external to the client; this helps people view their concerns as amenable to change rather than being an integral part of themselves (and so more difficult to change).

Stage 6: Stabilisation

If you have ever heard the phrase, “two steps forward and one step backward”, then you are aware of the seeming see-saw nature of change. People can implement even major changes in their lives, but in order to consolidate them, they need time to adjust their perspectives in more effective, hopeful directions. Thus, trying to restrain the client from going too fast and building in predictions of possible backsliding can help keep clients from becoming discouraged if permanent change does not happen as quickly as they wish.

Stage 7: Termination

The treatment finishes at Stage 7, with termination often being initiated by clients, who realise that they have met their treatment goals. Solution focused therapy focuses on resolving presenting problems rather than childhood issues; it does not try to change the client’s personality in a significant way. Thus, it acknowledges that clients may return for additional treatment; they are reminded that this is an option. Despite that, solution focused therapy may often go beyond the resolution of immediate concerns. As people feel heard and are praised for their efforts, they develop confidence and a greater awareness of their strengths and resources, leading to becoming more capable of resolving their own difficulties in future (stages from Seligman, 2006).

Conclusion

Solution focused therapy works as a therapy approach where a timely solution to a problem trumps deep analysis of it. This post-modernist, constructivist therapy asks therapists to create a positive expectancy for change, trusting the client’s truth and focusing on their preferred futures. A future orientation, a focus on strengths, acceptance of the inevitability of change, simplicity, and an understanding that “there is no resistance” can all help propel client and therapist successfully through the seven stages of therapy, which we briefly outlined.

Solution focused therapy training

This article was adapted from Mental Health Academy’s solution focused therapy training course, Solution-focused Therapy: The Basics. This 3-hour course examines the basic concepts and techniques of solution focused therapy, including its stages, limitations and contributions.

Other solution focused therapy training courses you may be interested in:

- Solution-Focused Narrative Therapy with a Mother and Daughter

- Solution-Focused Narrative Therapy with an Adolescent

- Intimate Partner Violence Solution-Focused Trauma Care

- Interviewing for Happiness: How to Weave Positive Psychology Magic into the Initial Clinical Interview

Note: Mental Health Academy members can access 500+ CPD/OPD courses, including those listed above, for less than $1/day. If you are not currently a member, click here to learn more and join.

Key takeaways

- Changes in the global healthcare scene in recent decades have paved the way for solution focused therapy, which prioritises timely solutions to problems over deep analysis of them.

- This post-modernist, constructivist therapy asks therapists to trust that clients have within them the resources for change, so a strengths-based, future-focused approach which seeks simplicity and looks for exceptions to the awful situation is utilised.

- Core concepts of solution focused therapy include: Solutions are not necessarily related to problems; Maintain a future orientation; Focus on strengths; Change is inevitable; Experiences are not black-and-white; There is no such thing as client resistance; Simplicity is key.

- The collaboratively-planned treatment proceeds in seven stages, from identifying a solvable complaint through to stabilisation and termination.

References

- Ackerman, C. (2017). What is solution focused therapy: 3 essential techniques. Positive Psychology Program. Retrieved on 24 January, 2018, from: https://positivepsychologyprogram.com/solution focused-therapy/

- Archer, J., & McCarthy, C.J. (2007). Theories of counselling & psychotherapy: Contemporary applications. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Education, Inc.

- De Shazer, S. (1985). Keys to solutions in brief therapy. New York: Norton.

- De Shazer, S. (1988). Clues: Investigating solutions in brief therapy. New York: Norton.

- Freedman, J., & Combs, G. (1996). Narrative therapy. New York: Norton.

- Hawkes, D., Marsh, T.I., & Wilgosh, R. (1998). Solution focused therapy: A handbook for health care professionals. Oxford, U.K.: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Lipchik, E. (2002). Beyond technique in solution focused therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

- O’Connell, B. (1998). Solution focused therapy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- O’Connell, B. (2006). Solution focused therapy. In Feltham, C., & Horton, I., Eds. (2006). The SAGE handbook of counselling and psychotherapy. London: SAGE Publications.

- O’Hanlon, B., & Weiner-Davis, M. (1989). In search of solutions: A new direction in psychotherapy. New York: Norton.

- Seligman, L. (2006). Theories of counseling and psychotherapy: Systems, strategies, and skills, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Weakland, J., Fisch, R., Watzlawick, P., & Bodin, A. (1974). Brief therapy: Focused problem resolution. Family Process, 13, 141-168.