In this article we unpack shame: what it is; how it presents in clinical mental health practice; and what interventions therapists can use to support clients dealing with it.

Related articles: The Stigma and Shame of Loneliness, Building Shame Resilience in Clients, What is Compassion-Focused Therapy?

Related discussion: How do you work with shame in therapy?

Jump to section:

Introduction

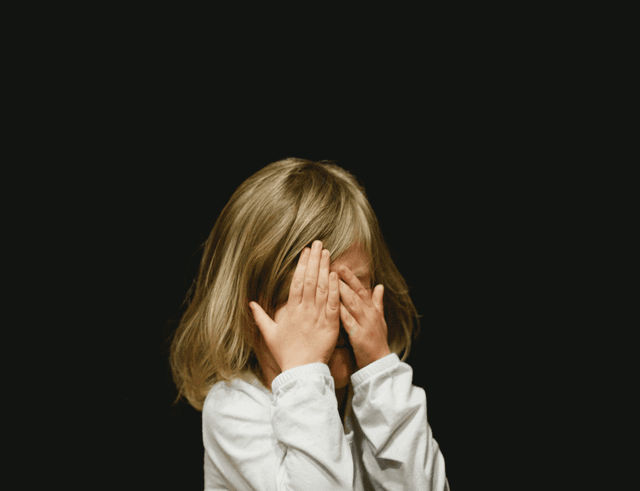

Shame is a deeply painful emotion rooted in a sense of self as fundamentally flawed, inadequate, or defective. Unlike guilt, which arises from feeling one has done something wrong, shame involves the pervasive belief that one’s entire being is inherently wrong or unworthy (Brown, 2023). As mental health professionals, understanding and effectively addressing shame is crucial, given its profound impact on clients’ mental and emotional well-being.

This article explores the concept of shame, including its definition, clinical presentation, and relationship with various mental health disorders. Additionally, it provides an overview of evidence-based therapeutic interventions and techniques, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), compassion-focused therapy (CFT), mindfulness-based approaches, narrative therapy, and attachment-based interventions. Short scripts, case studies, and clinical examples are included throughout to demonstrate how these approaches can be effectively applied in practice.

Unpacking shame

Clinically, shame is identified by self-criticism, chronic feelings of inadequacy, perfectionism, withdrawal, and self-sabotaging behaviours (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). It is considered one of the most powerful emotions influencing human behaviour, significantly shaping an individual’s self-concept and relational patterns. Shame often operates covertly, underpinning diagnoses like depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD, personality disorders (particularly borderline and narcissistic), substance abuse, and eating disorders (Gilbert & Simos, 2022). It is intrinsically tied to early developmental experiences, often arising from adverse childhood environments characterised by neglect, criticism, harsh parenting, abuse, bullying, or emotional invalidation, leading to long-term psychological scars (Van Vliet, 2008).

Shame can become internalised, manifesting in adulthood as a persistent sense of inadequacy, unworthiness, and vulnerability to criticism. Research has shown that unresolved shame can significantly impede therapeutic progress, reinforcing negative self-perceptions and maintaining maladaptive coping strategies such as avoidance, substance use, or self-harm (Archway Behavioral Health, 2024).

What shame looks like in clients

Clients experiencing intense shame often present with profound emotional distress, difficulties maintaining intimate and social relationships, avoidance behaviours, and pervasive negative self-talk. Shame frequently manifests as a fear of exposure, leading clients to isolate themselves or maintain superficial relationships. Behaviourally, clients may avoid eye contact, minimise or dismiss personal achievements, excessively apologise, or strive for unrealistic perfectionism. Shame often underpins defensive responses such as anger or hostility when clients perceive their vulnerabilities have been exposed.

For example, Anna, a 32-year-old client diagnosed with generalised anxiety disorder, reported constant self-doubt and fear of judgment, avoiding social interactions due to fears of humiliation rooted in childhood criticism from her parents. Similarly, Mark, a 40-year-old executive, consistently presented as confident and accomplished but privately struggled with debilitating self-criticism and perfectionism, fearing exposure as an ‘imposter’ (related: Taming Imposter Syndrome: Strategies for Therapists). His intense shame was linked to childhood bullying and severe parental criticism.

Studies illustrate the broad impacts of shame on mental health. A systematic review by Kim, Thibodeau, and Jorgensen (2011) showed that shame was a significant predictor of depressive symptoms and social anxiety disorder. Moreover, a meta-analysis by Tangney & Dearing (2002) found robust associations between chronic shame and personality disorders, particularly borderline personality disorder, highlighting shame’s role in emotional dysregulation, self-injury, and suicidal ideation. These studies underscore the critical importance of clinicians’ attentiveness to shame in therapeutic practice.

Interventions and techniques for addressing shame

Effective shame interventions target cognitive restructuring, emotional processing, relational repair, and self-compassion cultivation. The following are practical interventions therapists can utilise, illustrated with case examples.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

CBT interventions help clients recognise and challenge maladaptive shame-driven beliefs. A CBT technique particularly effective in shame work is thought records:

Case example – Anna:

- Therapist: “Let’s examine the thought ‘I’m fundamentally unlovable’. What evidence supports this belief, and what evidence contradicts it?”

- Anna: “Well, my parents always criticised me.”

- Therapist: “Does this criticism accurately define your worth or reflect their own struggles and limitations?”

In Anna’s case, a thought record helped her distinguish parental criticism from her intrinsic value, reducing anxiety and enhancing social engagement.

Compassion-focused therapy (CFT)

Developed by Gilbert (2021), compassion-focused therapy addresses shame by nurturing self-compassion. Central to CFT is cultivating compassionate self-talk and imagery exercises:

Case example – James (a 45-year-old with severe self-critical depression):

- Therapist: “Imagine a compassionate figure speaking to you. What might they say about your worth?”

- James: “They would say I’m worthy, even if I make mistakes.”

- Therapist: “How does hearing that compassionate voice affect your sense of shame?”

Jamesa experienced significant shame reduction through compassionate imagery, enabling him to reconnect with family and work.

Mindfulness-based interventions

Mindfulness fosters a non-judgmental awareness of shame’s transient emotional experience, reducing its overwhelming impact:

Case example – Maria:

- Therapist: “Notice the physical sensations of shame in your body without trying to change them. What do you observe?”

- Maria: “It feels heavy in my chest.”

- Therapist: “Observe that sensation compassionately, acknowledging it as part of your experience, but not the entirety of who you are.”

With mindfulness practice, clients like Maria, who previously avoided emotions associated with trauma-induced shame, gradually built resilience and emotional tolerance.

Narrative therapy

Narrative therapy helps clients rewrite shame-saturated stories, empowering new self-concepts:

Case example – Miriam:

- Therapist: “How has the story ‘I’m not good enough’ influenced your life? How might your story change if shame didn’t dictate your actions?”

- Miriam: “I’d feel freer to take risks and connect more authentically.”

- Therapist: “What might your new story be?”

For Miriam, narrative therapy facilitated redefining herself as resilient rather than flawed, significantly alleviating her social anxiety. Related: In this article we explore how this approach can be useful when working with First Nations Australians.

Attachment-based interventions

Since shame often originates in attachment wounds, interventions fostering secure therapeutic attachment are essential. Therapists can model acceptance and validate the client’s emotional experiences, creating reparative relational experiences:

Case example – Daniel:

- Therapist: “It makes sense you feel this way given your experiences. You deserved more compassion and understanding.”

Such validation helped Daniel, whose shame stemmed from childhood neglect, develop healthier adult attachments and improved self-worth. For more tips on how to validate and reassurance clients, read this article.

Case study: Integrating approaches to best support a client

Sarah, a 27-year-old woman, presented to therapy with a history of eating disorders, anxiety, and chronic shame related to childhood emotional abuse from her mother. During the initial assessment, Sarah expressed intense feelings of worthlessness and a pervasive fear of rejection and abandonment. She described significant emotional distress, social isolation, perfectionistic tendencies, and difficulty in maintaining healthy relationships.

Initial assessment

To gain a comprehensive understanding of Sarah’s emotional landscape and identify key therapeutic targets, the therapist began by exploring the origins and impacts of her feelings of shame. The following exchange highlights how Sarah initially articulated her struggles and the therapist’s empathetic response aimed at validating her experiences:

- Sarah: “I feel constantly judged, like I’m never good enough. I obsess over my body image and worry excessively about disappointing others.”

- Therapist: “It sounds like these feelings of shame and inadequacy have been impacting your life significantly. Can you recall when these feelings began?”

- Sarah: “It started when I was a child. My mother was extremely critical, constantly pointing out flaws in my appearance and behaviour.”

Therapeutic progress

To illustrate the implementation of an integrative approach in therapy, the following example maps Sarah’s journey through a series of clinical stages. This progression demonstrates how specific interventions were selected based on her evolving needs and responses. It highlights the significance of sequencing therapeutic techniques and adapting them over time to support deeper emotional processing and sustained change.

Sessions 1-4: Establishing safety and validation (attachment-based)

These sessions were designed to create a secure and attuned therapeutic alliance, essential for working with clients with histories of relational trauma. By consistently validating Sarah’s emotions and experiences, the therapist helped her begin to externalise the shame and recognise its developmental origins. This phase laid the foundation for deeper emotional processing.

The initial sessions focused on creating a safe therapeutic environment and validating Sarah’s emotional experiences. For example:

- Therapist: “Given your experiences, it’s understandable you feel this way. It was unfair for you to carry such harsh judgments from a young age.”

- Sarah (tearfully): “It’s relieving to hear someone acknowledge that.”

Sessions 5-10: Cognitive restructuring (CBT)

With increased safety established, therapy shifted toward identifying Sarah’s core beliefs and introducing techniques to challenge maladaptive cognitions. Thought records and Socratic questioning helped Sarah begin to observe the internalised voice of shame and evaluate its credibility, fostering cognitive flexibility.

CBT techniques, including thought records, were introduced to help Sarah identify and challenge distorted beliefs about herself. For example:

- Therapist: “Let’s examine the thought, ‘I’m worthless if I’m not perfect.’ What evidence supports this belief, and what evidence contradicts it?”

- Sarah: “My mother’s criticisms support it, but my friends often say I’m kind and caring, which contradicts it.”

Sessions 11-15: Cultivating self-compassion (CFT and Mindfulness)

As Sarah developed insight into her shame-based beliefs, these sessions focused on building a more compassionate relationship with herself. Compassion-focused imagery, soothing rhythm breathing, and mindful awareness were used to cultivate emotional tolerance and rewire the internal critic. These techniques helped Sarah access gentleness and care in place of harsh self-judgement.

Sarah was guided through compassion-focused imagery and mindfulness exercises to foster self-compassion and emotional tolerance. For example:

- Therapist: “Imagine a compassionate figure who fully accepts you. What does this figure say to you?”

- Sarah: “They say I’m enough just as I am.”

Sessions 16-20: Reauthoring life narratives (narrative therapy)

Having strengthened her internal resources, Sarah was ready to deconstruct dominant shame-based narratives and reauthor her identity. Narrative therapy encouraged exploration of alternative storylines that emphasised resilience, courage, and growth. This reframing process supported integration of new self-concepts aligned with her values and capacities.

Therapy involved rewriting Sarah’s self-narrative, shifting from a shame-based identity to a strengths-based narrative. For example:

- Therapist: “How would your life change if your story was about overcoming adversity rather than being defined by shame?”

- Sarah: “I’d feel stronger and more capable.”

Outcomes

Over eight months, Sarah reported significant reductions in her feelings of shame and anxiety, improvements in self-esteem, and greater emotional resilience. Her eating behaviours normalised, and she became more engaged in meaningful relationships, experiencing deeper intimacy and less fear of rejection. By integrating various therapeutic approaches, Sarah successfully addressed deep-seated shame, demonstrating sustained emotional healing and personal growth.

Conclusion

Shame is a pervasive, often hidden issue significantly influencing various mental health presentations. Effective clinical intervention involves understanding its cognitive, emotional, and relational dimensions. Integrative approaches combining cognitive restructuring, mindfulness, compassionate self-engagement, and attachment repair are especially effective. Addressing shame directly in therapy fosters deep emotional healing, improving overall psychological functioning and relational health.

Key takeaways

- Shame is distinct from guilt, rooted in beliefs of intrinsic inadequacy.

- Shame underlies numerous mental health conditions and often originates in attachment trauma.

- CBT, CFT, mindfulness, narrative, and attachment-based interventions effectively address shame.

- Integrated approaches yield the best outcomes, promoting lasting emotional and relational healing.

Questions therapists often ask

Q: How do I differentiate shame from guilt in a way that actually shifts the clinical conversation?

A: Name the direction of the emotion. Guilt points to a behaviour that violated values; shame targets the whole self. Bringing this distinction into the room helps clients see that their internal attack isn’t a moral compass but a learned survival response. That framing often reduces the emotional “fog” and opens space for self-compassion work.

Q: Clients often hide their shame well. What’s the most reliable way to surface it without triggering collapse?

A: Track the micro-signals—downward gaze, shrinking posture, sudden quietness, or humour used as a shield. Rather than confronting directly, reflect the relational impact (“I notice you pulled back just then—can we go slowly with that?”). Safety is the intervention. When clients sense you can hold the discomfort without flinching, they risk showing more.

Q: How do I keep from inadvertently reinforcing shame when exploring painful material?

A: Stay out of the “why did you do that?” lane. It feeds the client’s internal prosecutor. Use process-oriented curiosity: “What was happening for you then?” or “What did you need in that moment that you didn’t get?” That moves the focus from defect to context and reduces the client’s impulse to defend or shut down.

Q: Shame tends to be global and sticky. What’s an effective way to start loosening its grip?

A: Break it into parts. Ask the client to describe the specific moment they first felt the sense of being “wrong.” Anchor it in time, place, and relationship. Once the shame becomes an episode instead of an identity, you can map the old conditions under which it formed and challenge its present-day authority.

Q: Some clients intellectualise shame to avoid feeling it. How do I gently reintroduce emotional contact?

A: Keep them in the body. Invite them to notice sensations—heat, tightness, heaviness—as simple data rather than verdicts. Pair this with grounding or paced breathing. That combination reduces overwhelm and helps them experience the emotion in tolerable doses, which is where deep repair work actually happens.

References

- Archway Behavioral Health. (2024). Breaking free from shame: A pathway to mental health healing. Author. Retrieved on 3 April 2025 from: Breaking Free from Shame: How to Heal & Reclaim Mental Health

- Brown, B. (2023). Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience. Penguin Random House.

- Gilbert, P., & Simos, G., Eds. (2022). Compassion Focused Therapy: Clinical Practice and Applications. Routledge.

- Kim, S., Thibodeau, R., & Jorgensen, R. S. (2011). Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: a meta-analytic review. Psychological bulletin, 137(1), 68–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021466

- Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and Guilt. Guilford Press.

- Van Vliet, K. J. (2008). Shame and resilience in adulthood: A grounded theory study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(2), 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.2.233